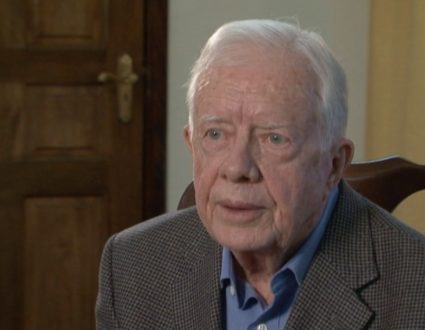

- Geoff Bennett:Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for about 25 percent of all disease in the world, yet it has just 3 percent of the health care work force needed to treat it. There are not enough medical and nursing schools, and many of the continent’s graduates are recruited to wealthier countries, where health care systems are also understaffed.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has a report on one effort to educate African providers who will stay and serve their communities. It’s part of his series Agents for Change.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:They hiked for nearly an hour. A small group of medical students headed to a village not accessible by car.Their professor accompanied them, but the teacher today was a woman with little formal schooling. When it comes to health issues in this remote community in Northern Rwanda, village health workers like Jeanne Mukarurangwa have the keenest knowledge and training to watch for telltale signs of problems.

- Jeanne Mukarurangwa, Community Health Worker (through interpreter):Malaria is a big problem here. I am mainly focused on women and babies. We register all women who are pregnant, and I will visit them three times during their pregnancy.

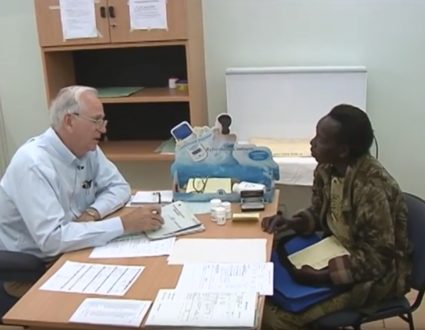

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:After a quick briefing, they were off to the home of a couple expecting their first child.Dr. Akiiki Bitalabeho, Professor, University of Global Health Equity: We do not want students to come in and be seated in front of a patient giving them information that is from a textbook.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Professor Akiiki Bitalabeho says textbooks teach how to treat disease. On the other hand, real-world experience teaches how to treat the patient and why a textbook prescription may not work, for example.

- Dr. Akiiki Bitalabeho:They might not be taking their medicines because, when you take them on an empty stomach, it pains. Do you know that they woke up at 4:00 a.m. to be at your hospital at 8:00 a.m.?

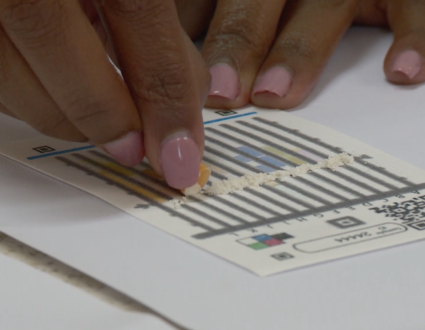

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:On this day, Jeanne Mukarurangwa used her well-worn illustrated binder to make sure her patient, Solange Manakarame (ph), got important information to ensure a safe pregnancy.She emphasized the importance of taking iron pills and eating a healthy diet, though that is not easy off a small plot of land and daily wage work when available.

- Jeanne Mukarurangwa (through interpreter):In such extreme poverty, it’s not easy for people to afford meat, but I tell them to get eggs or milk, which they can afford.

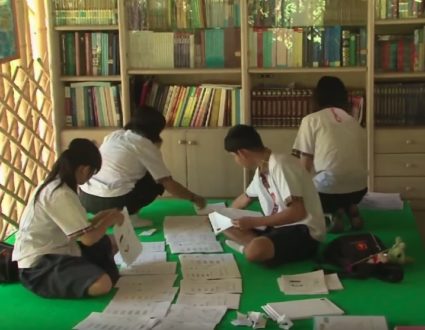

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:The students will spend a lot of time in village settings. Back on campus, they spend their first six months in non-medical coursework, like anthropology and history, before beginning six intense years that lead to degrees in medicine and global health delivery.The University of Global Health Equity was inaugurated in 2019, brainchild of the late Harvard anthropologist and physician Paul Farmer. He co-founded the group Partners In Health, which has brought world-class care to some of the world’s remotest places. That same philosophy brought this medical school to Butaro in Northern Rwanda.Dr. Abebe Bekele, Dean, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Global Health Equity: All over the world, medical schools are set up in capital cities.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dr. Abebe Bekele, a thoracic surgeon, is dean of the School of Medicine at the University of Global Health Equity, or UGHE.

- Dr. Abebe Bekele:UGHE is a complete opposite to that. It’s closer to the community, to the vulnerable, to the poor.

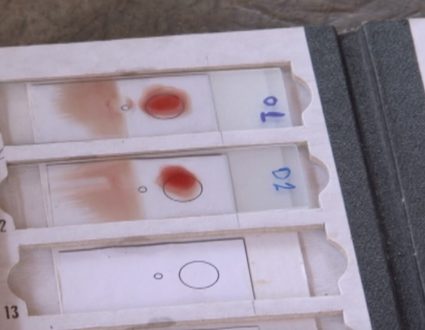

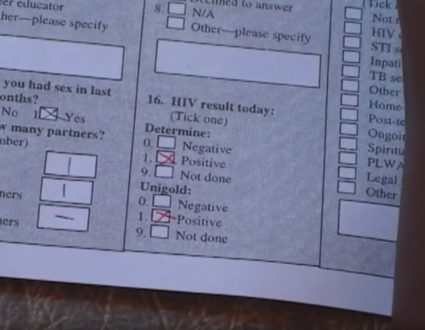

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:It all began in 2011 with a world-class hospital in Butaro. It has the only oncology center in the entire country outside the capital, Kigali, which is too distant and expensive for most rural patients.Most cancer patients in this country and many others simply go untreated. Take just the example of breast cancer, where, in high-income countries, more than 90 percent of patients survive five years after their diagnosis. The equivalent figure in sub-Saharan Africa is 40 percent.Jennifer Dickson McKunde, Student, University of Global Health Equity: I started out in the oncology ward, where I was just meeting a lot of patients coming in and out, coming in and out.I think she has breast cancer metastasis.And it’s so sad to see how many of them come at late stages and are just left on palliative care.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:That said, third year student Jennifer Dickson McKunde, who’s from neighboring Tanzania, says every patient, including a woman whose condition is incurable, gets the best available therapy to ease their pain and suffering, a marked departure from the practice and philosophy in many low-resource settings.

- Jennifer Dickson McKunde:In Tanzania, she wouldn’t be able to get her chemo for free. And they wouldn’t even recognize that that chemo is even useful or, as they would say, worthwhile for her. McKunde is among 42 students from nine African countries, 70 percent of them female, selected each year from nearly 1,600 applicants.And because it’s much needed in rural settings, their education emphasizes emergency and trauma care. The mannequins can actually accurately simulate pain points. The goal is to train doctors who are also advocates for equitable care.Students sign contracts agreeing to work for five years after graduation in an underserved area. In exchange, they get a free ride here.

- Dr. Abebe Bekele:Young people with the heart, the brain and the hands to practice medicine, in that order, should be given the opportunity to do so.

- Dr. Nitasha Sharma, Trauma Surgeon, Massachusetts General Hospital:OK, so we’re starting to see some structures here. What are we seeing?

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:And the university has partnered with some of the world’s top institutions that regularly send guest faculty, like Dr. Nitasha Sharma, a trauma surgeon at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital.

- Dr. Nitasha Sharma:You want to hold your probe from the top.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:One concern is how such interactions might influence the aspirations of the future doctors. Some 5,500 physicians from sub-Saharan African nations now work in the United States alone.

- Dr. Nitasha Sharma:Every trauma team needs a team leader.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Will these students resist the lure?Given the economic and financial realities of our world today, they get an offer to go to North Carolina, Harvard, Edinburgh at enormously large salaries?

- Dr. Abebe Bekele:Yes, absolutely. We can’t deny that.

- Dr. Nitasha Sharma:Is everybody ready?

- Men and women:Yes.

- Dr. Abebe Bekele:Every faculty conveys that message, that God put them in this place for a reason. There is some sacrifice this generation has to pay for the betterment of the next generation. We have six-and-a-half years to make sure that’s done.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:The university does have agreements with governments of the students’ countries to ensure its graduates will receive livable wages. Students we spoke to were determined to stay in their home countries.David Saizay is from the civil war-ravaged West African nation of Liberia.David Saizay, Student, University of Global Health Equity: I would like to work with my Ministry of Health so that we can be able to put things in place for people that can’t afford basic medical aids, basic medical care.Jocelyn Nzisabila says she’s determined to be part of the rebuilding efforts in her native Rwanda.Jocelyn Nzisabila, Student, University of Global Health Equity: I don’t see anything which is more fulfilling than actually serving your community. If I’m not going to be part of the solutions, who’s going to do it?

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Jennifer Dickson McKunde’s role model is her mother, a physician who returned to serve in Tanzania.

- Jennifer Dickson McKunde:Most of her education, she was able to attain it abroad, and she always mentioned that there’s nothing better than home and helping your people. And, for me, myself, I felt — I feel the same way.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dean Abebe admits this university faces tough challenges, counting, among other things, on philanthropic funding. But, he says:

- Dr. Abebe Bekele:Three hundred fifty years back, Harvard was just a small building. Look at it now. I think they had that vision. We probably may not see it in our lifetime, but this is a beacon of hope for medical education in the continent.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:The University of Global Health Equity will graduate its first cohort of medical and global health practitioners in 2026.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Butaro, Rwanda.

- Geoff Bennett:And, tomorrow, we will look at an effort to improve and sustain agricultural production in Africa.And we should say that Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

The University of Global Health Equity

fighting the brain drain

Africa already struggles to produce enough health care workers to meet the need, and many of the continent’s graduates are recruited to wealthier countries after graduation. In this report we highlight one effort to educate African providers who will stay and serve in their home countries.

25%

of the world’s burden of disease is in Africa

3%

of the world’s health care workforce are in Africa