- Amna Nawaz:It’s a taboo topic and an age-old practice across several countries and religious traditions in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. An estimated 230 million women and girls are subjected to genital mutilation, or cutting.

- Geoff Bennett:Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Senegal, where one group has had success in getting thousands of African communities to abandon the practice.A note that the group does not receive any current funding from USAID, so it’s unaffected by cuts to that agency.

- And a warning:This story contains some explicit references.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:In the small town of Dialakoto recently, there was a coming-out party for several nearby rural communities, a boisterous and until a few years ago very unlikely gathering called a declaration attended by elected, traditional and religious leaders.One after the other, these communities came forward to proclaim that they were abandoning female genital mutilation, or cutting. It’s a removal, partly or wholly, of the clitoris, a practice some scholars trace to beliefs about chastity until marriage or even hygiene, dating back some 2,000 years, one that the U.N. and governments have long tried to eradicate.

- Molly Melching, Founder, Tostan:The new rule is you do not, you do not cut your daughter.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:On a bumpy ride to the declaration, I asked Molly Melching what’s bringing about change here. The key difference, she says, it’s not a directive to eradicate, but a decision to abandon cutting.

- Molly Melching:We need to abandon ourselves. It’s not because someone tells us to.

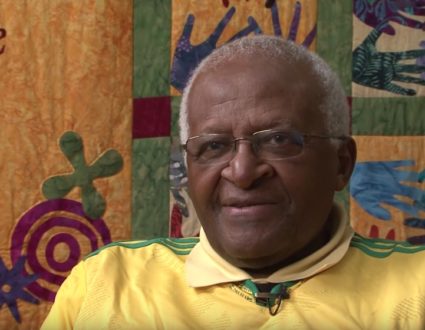

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Melching is globally recognized as founder of a group called Tostan, or Breakthrough, best known for helping communities across several African countries abandon FGC. It’s not exactly what the Danville, Illinois, native set out to do when she moved to Senegal as a student, then Peace Corps volunteer, a long time ago.

- Molly Melching:I would not have dreamed that I would be here 50 years, although this is a magical country. It’s beautiful.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:She began in education, working to develop children’s reading materials in local languages. In Senegal, books, if available at all, were in French, the former colonial language that few can read or even speak.With a small grant, she began in the village of Sam Ndiaye, where she also lived for three years.

- Molly Melching:We saw this great hunger for education among the populations. They wanted to learn to read and write. They wanted to learn more about health and how they could prevent illnesses.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:It grew into adult education, first for women, eventually everyone, and focused on the causes of various health problems.

- Molly Melching:They wanted to learn what happened to them. We didn’t even bring up FGC until much later in the program. And, meanwhile, they had learned what are the practices that may harm and lead to problems later on in life.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:As FGC came up organically, she says, the newly acquired health education helped link the practice to its myriad painful short and long-term consequences, infections, hemorrhage, even sterility and death.Tostan’s approach includes teaching about human rights and, in discussing FGC, she says, the message was one of support, not shame.

- Molly Melching:We understand that you did this not because you wanted to harm your daughters. And no woman wants that her daughter not be able to marry because no one respects her. So they had no choice. And suddenly they realized that together, collectively — today, we’re going to a declaration of 29 villages. They have come together to collectively decide that this is no longer the expectations.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Although she’s not active in the day-to-day running of Tostan any longer, Melching is a celebrity, reconnecting here with many alumni from its education programs, women like 52-year-old Doussou Sissao, who have carried the torch forward after attending one of the earliest declarations.

- Doussou Sissao, Social Mobilizer, Tostan (through interpreter):In 2003, we did a declaration for many communities around here because of that desire to see to end violence and practices which are harmful to people, to girls. So now we need to even go to other places where people are still practicing.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Her own three grand-daughters are now free of the pain endured by their elders. Sissao is one of hundreds of so-called social mobilizers for Tostan, traveling to communities to urge abandonment.How did the men react to all these changes?

- Doussou Sissao (through interpreter):In the beginning, it was hard because the men didn’t know what goes on when you practice this female tradition. They just accepted that that was what was to be done.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:We visited Sounkarou Diambang, village chief, now in retirement, who recalls being approached by women in the community. He called together religious leaders. Senegal is a predominantly Muslim country.

- Sounkarou Diambang, Dialakoto Village Chief (through interpreter):They said, let us look in the Koran and see where it is written that women must go through this. And they found nowhere where it said that they must be cut.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:That interpretation removed a significant hurdle to abandoning FGC in many communities and drew the support of men. Indeed, many social mobilizers and Tostan staff are male, many driven by memories of a loved one’s suffering.Melching took time to stop by the family of one late campaigner, Boubou Sall (ph), who years earlier had lost an 8-year-old daughter.

- Molly Melching:He thought when she got a fever two weeks after she got the FGC operation, he thought that it was malaria, and so he treated her for malaria because he had the pills with him. And when she got worse, he then was told that she had tetanus and it was too late.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:It was an emotional reunion with Sall’s family. The Tostan manual he used, in the local Mandinka language, was still on the shelf 12 years after his death.

- Molly Melching:This was the hygiene and health module where Boubou Sall said he learned the transmission of germs and realized that his daughter died because she was cut with a knife that was not sterilized.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:He traveled village to village with his story and guidebook, urging people at Tostan classes to attend a declaration event like the one in Dialakoto.These are a critical step in normalizing a social change. For communities considering abandoning female genital cutting, one last concern is, will they be ostracized for abandoning a time-honored tradition? The hope from these gatherings is that they can be an instant cure for that stigma.As one person put it to me, everyone now sees that everyone else is doing it. Melching says that that decision to abandon is just one part of a holistic approach to improving life in communities. She took me to Sam Ndiaye, the village where it all started decades ago. After a ceremonial welcome, we were shown the latest vision board, a development wish list for the next 10 years, illustrated by hand in a community when not all adults can read.The most pressing priority, adding a doctor to the nurse who now heads the health center they brought to the village a few years ago.So none of this existed when you moved into this village?

- Molly Melching:No, this was all empty space here.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:Its spartan but a solid building block toward better health.The key to Tostan’s success, she says, has been to play a supporting, not directing role that’s so common in aid work today. Help communities write a grant for example, or provide health information and let communities decide for themselves.How many villages have abandoned now?

- Molly Melching:Over 9,500.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:In eight countries?

- Molly Melching:In eight countries.

- Fred de Sam Lazaro:A small dent in a global problem, Melching says, but a lesson that development works best from the inside out.For the “PBS News Hour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Dialakoto, Senegal.

- Amna Nawaz:And a reminder that Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Development from the Inside Out

How it works

More than a decade ago, we visited Senegal to report on a program that was making remarkable progress in the global effort to end the ancient practice of female genital cutting. We wanted to find out what made this program work where so many other efforts had failed. The secret, Tostan’s founder Molly Melching says, is what she calls “development from the inside out.”

In this report, we explore the Tostan method—a transformative approach that combines literacy, health, and human rights education leading thousands of villages across Africa to collectively abandon cutting and work together to build a vision for community improvement.

An estimated 230 million women and girls are subjected to genital mutilation.

More than 9,500 villages have abandoned the practice across eight countries

” “They have come together to collectively decide that this is no longer the expectation.”

-Molly Melching

Why it Works

The key to Tostan’s success, Melching says, has been to play a supporting, not directing role that’s so common in aid work today. Help communities write a grant for example, or provide health information and let communities decide for themselves.