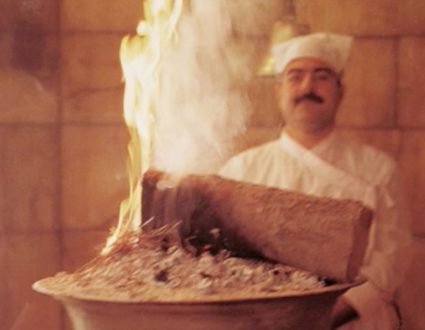

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Kashmir has long been known for its peaceful vistas but for the 13 million inhabitants this mountainous region has been anything but peaceful. It is one of the world’s most militarized places. India alone has an estimated 600,000 troops in the part it controls, four times the number of American soldiers who were in Iraq at the height of that war. Although it has a two-thirds Muslim majority, Kashmir as a whole is quite diverse, the southern region mostly Hindu, the northeast Buddhist. But for six decades this province with a land mass the size of Idaho has been bitterly fought over by India and Pakistan.

It all dates back to 1947, when the departing British decided to partition the newly independent India. Muslim majority areas were to form the new republic of Pakistan. But Kashmir had a Hindu ruler, and he opted under pressure to join India. That set off the first of three major wars between India and Pakistan, ending in a ceasefire with India controlling about two-thirds of Kashmir, Pakistan most of the rest. The so-called “line of control” that divided Kashmir has served as an international border for 65 years, but Kashmir has festered as a sore point between the Islamic republic of Pakistan and mostly Hindu India.

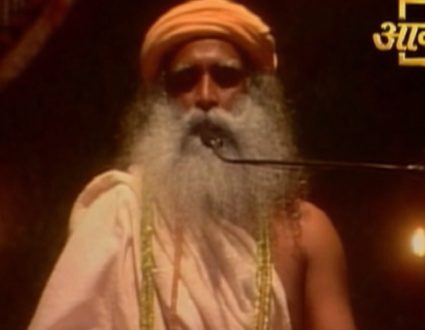

Although the conflict has long been cast in religious terms, Joseph Schwartzberg, a leading scholar on Kashmir, says it’s more complicated than that. And within Kashmir, he says, there’s a long tradition of tolerance.

PROFESSOR JOSEPH SCHWARTZBERG: The Hindus frequently attended religious ceremonies that were held by Muslims, and the converse was also true. In terms of actual day to day religious practices it was a fairly eclectic area, and the type of strident militaristic Islam that we think of when we think of, say, the Middle East—that was not present in Kashmir at all.

DE SAM LAZARO: That began to change in the 1980s in Indian-held Kashmir with more religious tension and extremism. Schwartzberg blames corruption, non-functioning local government, and meddling from India’s capital Delhi in local elections.

SCHWARTZBERG: India is a pretty good functioning democracy in most parts of the country, but with respect to Kashmir it was exceptional. They felt that they couldn’t afford to lose elections. They managed to rig election after election, and the people simply got fed up. In 1987—and it was a pretty corrupt administration, so the people just had it— they initiated a series of demonstrations which were put down with a heavy hand, and in 1989 it really got out of hand, and the Indian government moved in in force.

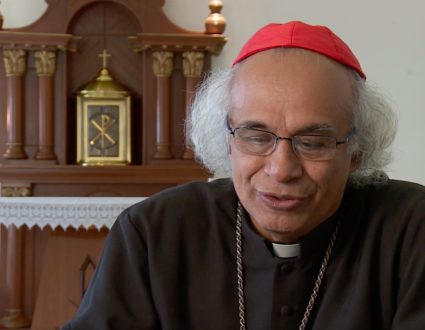

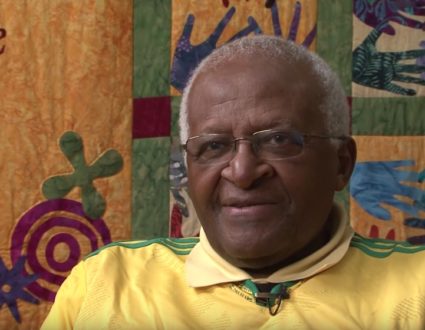

DE SAM LAZARO: The clampdown triggered a militant separatist insurgency—or vice versa, depending on who is telling the story. India has blamed Pakistan, especially its intelligence service, and Islamist extremist groups. Pakistan says it offers only moral support for the insurgents. Groups like Human Rights Watch blame militant groups, but they also finger Indian security forces for widespread abuses under the guise of rooting out militants. India insists that most are infiltrators from Pakistan-held regions and beyond. Tens of thousands of civilians have died or gone missing. Kashmir’s grand mufti, the top religious leader recognized by India’s government, also blames both sides for excesses, and his numbers are much higher.

Bashir Uddin Ahmad, Grand MuftiBASHIR UDDIN AHMAD (Grand Mufti): Since 1989, when the situation became more critical, hundreds of thousands of people are missing and hundreds of thousands more have been killed. We have no knowledge of where they are. The killing continues unabated, and the situation is still simmering.

DE SAM LAZARO: In recent years, the Kashmir dispute has taken on a new dimension as India has announced plans to build several dams, seeking hydro-electric power for its fast-growing economy. But Kashmir’s rivers also irrigate the breadbaskets of both India and Pakistan. So far there have been no problems sharing the waters under an internationally brokered treaty in 1960. However, Pakistan says the Indian dams could affect seasonal water flows to its farmland.

KAMAL MAJIDULLA (Pakistan Presidential Advisor): It’s devastating, because if the waters are not available to me in the quantities that I need them at the time that I need them, then I’m looking at a very low productivity of my agricultural sector.

DE SAM LAZARO: Pakistan has taken its protest to arbitration provided for under the Indus water treaty. India insists it is in full compliance. However, the fact that India, being upstream, could in theory manipulate flows could be politically toxic, particularly after the severe floods Pakistan has endured in recent years.

Hafiz Saeed is a man the US government has branded a terrorist and for whose capture it has offered a $10 million bounty. Saeed has blamed India for worsening the flooding. Pakistani presidential advisor Kamal Majidulla says such rhetoric resonates among farmers who are hurting.

MAJIDULLA: The farming community, which otherwise could look after their children, are unable to do, so the children have been going off and staying in madrassas instead of going to the local school system, because the madrassas feed them. I’m not saying all madrassas are bad. They do perform a social function, and some of them perform a very good social function, but a fair number of them are not. And this is where the cannon fodder comes from. So there is a direct linkage between water availability, low agricultural productivity, and the rise of terrorism.

DE SAM LAZARO: Officials in India’s capital Delhi say the Pakistani fears of water treaty violations are overblown. Ashok Jaitly, a scholar at a Delhi-based think tank, says the bigger threat is poor conservation and water mismanagement on both sides.

ASHOK JAITLY (Energy Resource Institute): If you had a cooperation based on good scientific river basin management of the Indus basin, and that’s where the Indus water treaty does not provide for it, it only provides for sharing of water. It does not provide for scientific integrated river basin management. If you could have that, then I think a lot, I won’t say all the problems would be solved, but a lot of the problems between India and Pakistan would be resolved, or could be resolved.

DE SAM LAZARO: Back in Kashmir, long squeezed as its two nuclear armed neighbors fight over it, Mufti Bashar Uddin says growing numbers want no part of either.

MUFTI UDDIN: As a religious leader, I would tell the people that if the option of independence is offered, that would be the best bet for Kashmir.

DE SAM LAZARO: That seems highly unlikely—both India and Pakistan reject the idea. So, to most analysts, does any quick resolution of the Kashmir stalemate. In recent months, there’s been a thaw in relations between India and Pakistan, with proposals to vastly increase the amount of trade across the border. Coincidence or not, Kashmir has enjoyed one of its quietest periods in years. The natural beauty is once again luring tourists. In 2011, more than one million visitors came here, most of them Indian. It remains to be seen whether and how much more tourism and commerce can repair 65 years of suspicion and upheaval.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro.

Disputed Land

Kashmir has long been known for its peaceful vistas but for the 13 million inhabitants this mountainous region has been anything but peaceful. It is one of the world’s most militarized places. Correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

Kashmir’s rivers irrigate the breadbaskets of both India and Pakistan.

So far there have been no problems sharing the waters under an internationally brokered treaty in 1960. However, Pakistan says the proposed Indian dams could affect seasonal water flows to its farmland.

“As a religious leader, I would tell the people that if the option of independence is offered, that would be the best bet for Kashmir.”