JUDY WOODRUFF:But, first: the last hurrah of a once-thriving Jewish community in one of the diaspora’s farthest-flung places.Fred de Sam Lazaro takes us to India.A version of this story aired on “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:In its nearly 900-year history, this synagogue had never seen an observance like this one. They came from four continents to this unlikely location, the coastal Indian city of Cochin, for the first Sabbath service in decades — and possibly the last one ever.A once thriving Jewish community of several thousand has mostly faded into a bittersweet history in the age of modern-day Israel, said Yeshoshua Sivan, a British-born Israeli.YESHOSHUA SIVAN, Israeli tourist: I’m very sad to see communities disappear. On the other hand, I’m very happy to see that after all these years of dispersion the prophecy of the return to the land of Israel is in my time being — I’m part of it — is being realized. At least we see the synagogues, we see the streets, we see how life was once here.

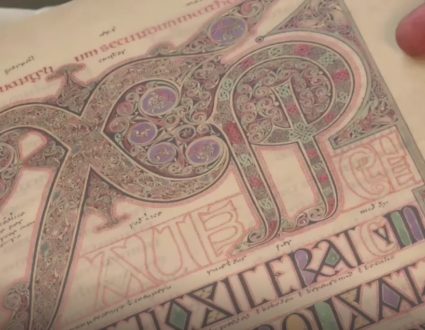

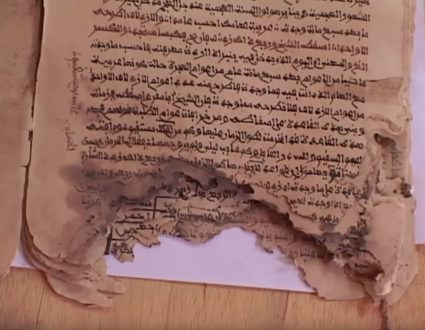

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Jewish life along India’s Malabar Coast dates back to the ancient spice trade that drew explorers from across the sea.They come now as tourists, but they came in ancient times to trade, and, in the case of some Jews, to settle — from Yemen, Mesopotamia, and later a few from Spain and Portugal after the Inquisition.Away from tourist enclaves, there’s a struggle to preserve what remains of the Jewish heritage here.I’m standing in what was the women’s section of a synagogue in Mala, about four or five miles in from the coastline. There was a thriving Jewish community here until 1955, when they decided, all of them, en masse, to emigrate to Israel. And they turned this building over to local municipal authorities.

C. KARMACHANDRAN, Historian:They were very good friends. They were very good neighbors. They were very good traders.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Some left for religious fulfillment in the new Jewish homeland, says retired Professor C. Karmachandran, who heads a local historic preservation committee. Others thought Israel had better economic prospects, he adds, but none left in fear. Scholars agree that there’s little history of anti Semitism in India.

C. KARMACHANDRAN:They were given all the protection by the rulers as well as the local people to maintain their culture, their religion, their belief and their practices, and this in fact is the living symbol of that particular lofty tradition.

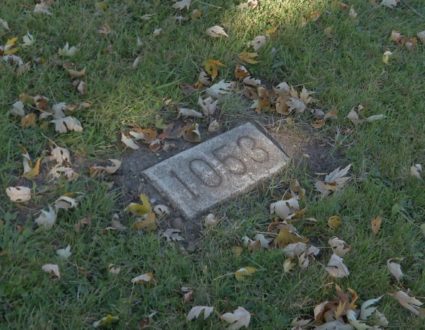

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:But even lofty traditions come under development pressure or suffer neglect. Already half the old Jewish cemetery has been appropriated for a stadium, Karmachandran complains.The rest is overgrown with weeds, where livestock graze. Fading memories breed indifference, he says, but in a time of growing religious tensions in India, it’s critical to preserve the heritage here.

C. KARMACHANDRAN:To keep it up for posterity.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For posterity.

C. KARMACHANDRAN:This is a lesson of tolerance.

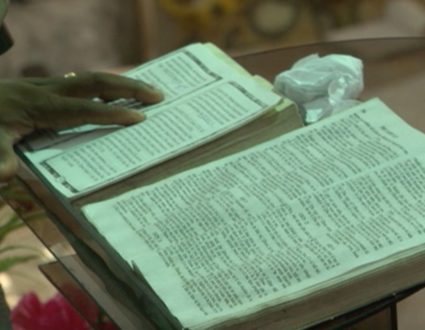

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Sixty-year-old Elias Josephai was made caretaker of the synagogue in Cochin. He’s one of the last remaining members of a community that numbers no more than a handful today.This is where school children sat?In the space where children once studied on the Shabbat, he runs a nursery and aquarium supply business. The synagogue proper served as a dusty warehouse when I first visited Josephai.And the scrolls from here are?

ELIAS JOSEPHAI, Synagogue Caretaker:In Israel.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Its sacred scrolls were donated years ago to a museum in Israel. Lacking the minyan or quorum of 10 men required for a Shabbat service, there hadn’t been one since 1972.

ELIAS JOSEPHAI:I cry every Shabbat, every holiday. I cry in my heart.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:About a year ago, Josephai shared that lament with some Israeli tourists who stopped by.ARI GREENSPAN, Tour organizer: And when he told us that they hadn’t prayed in that synagogue since 1972, I said to myself, I’ve got to come back with a group, with a quorum of 10 men.

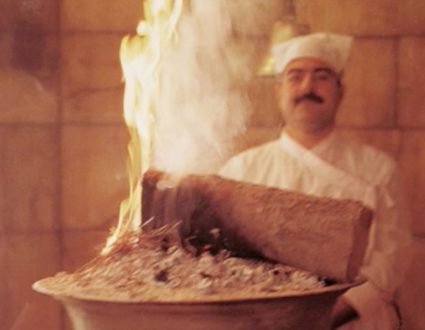

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Brooklyn native Ari Greenspan, a dentist and amateur chef now in Israel, did indeed organize a return tour of India’s Jewish communities, complete with a kosher menu.

ARI GREENSPAN:So here we have a traditional Jewish cook and a traditional Indian cook, Ravi, who’s been traveling with us all week, making sure that we have both strictly kosher and amazingly tasty kosher Indian food.

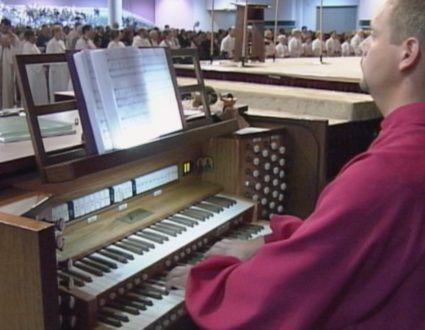

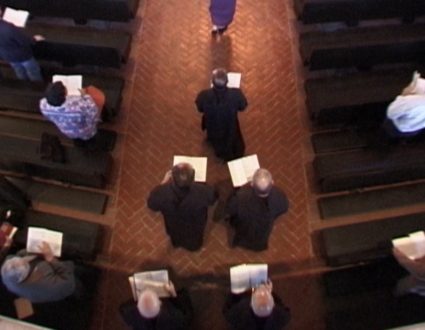

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:As they prepared the Shabbat meal, some of the 35 visitors took time for pre-Shabbat prayers. Most came here under the auspices of the U.S.-and-Israel-based Orthodox Union, which encourages Jewish heritage tours.

MICHAEL WIMPFHEIMER, Jewish Heritage Tourist:It’s still wonderful to go into a building which hasn’t been used in a very long time. At least you’re able to have it function again for the purpose a synagogue was meant, namely to hold a prayer service. It’s kind of a revitalization, even for a short time.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For Josephai, it was a dream 44 years in the making, as the visitors entered a sanctuary that had been spiffed up. They heaped praise on their host.

ARI GREENSPAN:You’re sort of on the cusp. He’s the last guy here, and when he goes — he should live to be 120 years old, right, but, when he goes, that’s it. Two thousand years of Cochin is gone.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Josephai actually plans to be gone in four years, retiring and settling, like all the rest, in Israel. It’s not an easy decision, leaving a land he holds dear and a place so influential in forming who he is.

ELIAS JOSEPHAI:I will keep my heart over here and then go. Always, I love India, but it is inevitable. One day, today or tomorrow, I have to leave the country, not because of the discrimination, but, as a Jew, to live, to be as a Jew.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Elias Josephai may well be that last Jew, the one who’ll turn out the lights on nearly a millennium of history in this place. For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro, in Cochin, India.

JUDY WOODRUFF:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A 900 Year Legacy

For 900 years there was a small Jewish community on India’s Malabar Coast, living at peace with its Hindu, Muslim and Christian neighbors. It was been a model of interfaith tolerance. But, as Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, the community has dwindled since the state of Israel was established, and now one of the last Jewish survivors, who maintains the local synagogue, says he plans to leave in a few years himself—for Israel.

Lacking the minyan or quorum of 10 men required for a Shabbat service, the Cochin synagogue hadn’t had one since 1972.

Tasty kosher Indian food

Ari Greenspan brought 35 mostly Israeli and American Jews to visit Cochin and hold a Shabbat service in the Cochin synagogue.

“One day, today or tomorrow, I have to leave the country, not because of the discrimination, but, as a Jew, to live, to be as a Jew.”