GWEN IFILL:Next: delivering cutting-edge medical care from a most unusual vehicle.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Vietnam. It’s part of his ongoing series Agents for Change.

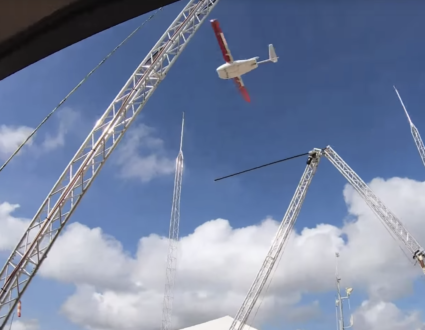

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Back in 1970, when this wide-body DC-10 first went into service, war was still raging all around this airport in Hue, Vietnam. In the town center, there are still reminders of the conflict that ended 40 years ago, including an exhibit that captured American military hardware, but at the airport a very different perception.The DC-10 crew got a flowery welcome. Then they quickly got to work on board.DR. AHMED GOMAA, Medical director: We convert this airplane into a fully equipped eye hospital, state-of-the-art facility. We have a team of 22 professionals covering all what is needed to run the hospital.

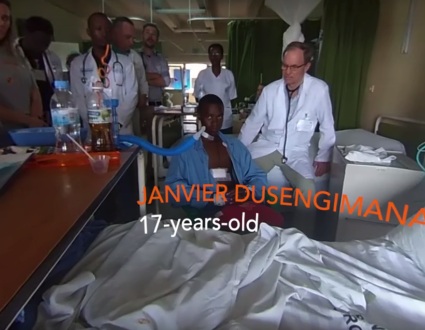

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dr. Ahmed Gomaa is medical director of the Orbis Flying Eye Hospital, started in 1982 with grants from the U.S. government and from corporate and individual donors. It has visited 92 countries. This is the sixth visit to Vietnam.Many of the staff are volunteers, including the pilots. Nurses and doctors do hands-on care during the week-long visit, but the main goal is training, to sustain care long after they leave, says California-based surgeon Mary O’Hara.DR. MARY O’HARA, Eye surgeon: This is very, very different than being the great white surgeon who comes in and does some magical surgeries and then leaves without imparting any of the magic to the surgeons in the community. It’s teaching the doctors the surgical skills to go forth and do good things for the community and also teach other doctors, so there’s a ripple effect.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:So, well before the plane arrives, Orbis has alerted local eye care providers, who in turn alert likely patients.For 8-year-old Thuy, it’s a rare chance at surgery for her strabismus, or lazy eye.

WOMAN (through interpreter):We took her to see the doctor four years ago.

MAN (through interpreter):We were afraid to even ask how much it would cost.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Thuy’s father is disabled. Her mother earns less than $2 a day gathering and selling recyclables.

CHILD (through interpreter):I hope the doctors can help me. I don’t want to be cross-eyed anymore.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Strabismus is common, affecting perhaps 4 percent of all people. Patients can lose sight in the wayward eye and depth perception. There also are painful psychosocial effects, says Dr. O’Hara.

DR. MARY O’HARA:We’re keyed to be attracted to symmetry and repulsed by asymmetry on a very subconscious level. And people who have crooked eyes tend to be down-rated in society.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Just because of the appearance of that person.

DR. MARY O’HARA:Right.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Six-year-old Van doesn’t seem affected by social stigma, at least not yet.

MAN (through interpreter):Her life is pretty normal. She gets teased a bit, but her life is pretty normal.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Van’s parents also struggle to make ends meet and cannot afford surgery.

MAN (through interpreter):We had been to a doctor three years ago. They said wait for a charity group to come.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The next day, they and others gathered at the local eye hospital for screening. About 75 patients are being screened here at the local hospital. Some 45 will be chosen for surgery or laser treatment, based on a variety of criteria. They need to be particularly good teachable cases. Young patients with good prognoses have priority, as do those in danger of losing their sight altogether.Orbis volunteers surrounded by local doctors and students assessed patients with various eye diseases, including diabetes-related conditions, glaucoma and strabismus.Thuy, it turns out, wasn’t a good candidate for surgery. Dr. O’Hara says she needs more patching therapy, in which the good eye is covered up, so the wandering one can be exercised.

DR. MARY O’HARA:We really need to have her in her glasses and have her amblyopia treated and then think about surgery.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The letdown was plain to see on the faces of Thuy and her mother.

WOMAN (through interpreter):Of course we’re sad, seeing my daughter sad. We were hopeful working with these people, so it’s a little sad that nothing came of it.

DR. MARY O’HARA:And is she otherwise healthy?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:It was Van’s turn.

DR. MARY O’HARA:See how much bigger the exotropia is here than down here?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:And happier news.

DR. MARY O’HARA:I would do 10-millimeter bilateral lateral rectus recessions.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Meaning Van would get surgery on both eyes to bring them into alignment.The next morning, as she and her father walked up to the airplane, lectures were already under way in what normally is the first-class section. It’s now a 48 seat classroom. In the back, the team led by Dr. O’Hara was preparing.

WOMAN:Are you ready? Does she have any allergies?

WOMAN:No.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:No allergies, and clearly no fear. As she underwent a 90-minute procedure, it was followed closely on video screens in the classroom.While there are more economical ways of teaching doctors, such as using video links or even flying trainees to Dr. O’Hara’s California hospital, Orbis says a key part of its mission is to raise awareness of eye disease, is often neglected amid myriad other challenges faced in developing nations.Dr. Gomaa says the plane’s sheer gee whiz factor attracts visits from influential officials in the host country

DR. AHMED GOMAA:The young doctors, a generation coming, is amazing, very good doctors. So, they need support. They need support. They need machines.

WOMAN:Slow. Good. Up. Beautiful.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Back in the operating room, Van’s surgery was wrapping up, with Dr. O’Hara guiding local surgeon Thao Phuong.

DR. MARY O’HARA:The surgery went fine. The person I was training on this particular surgery had done surgery before, and she was very good and attentive listening to instruction and following instruction.

DR. THAO PHUONG, Vietnam (through interpreter):Dr. O’Hara was very clear in her instructions. The whole process, from tiny things, from anesthesia, it was very detailed, step by step.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:She and other local doctors hope Orbis will help them expand care to allow families like Thuy’s to get help. For its part, Orbis needs a lot of money to run its operation, but it gets almost as much in kind through volunteers like pilot Bob Rutherford.

BOB RUTHERFORD, Pilot:You will see things that you never see in life. Young children who’ve never had vision, they have their sight restored. Those things really kind of pull at your heartstrings. It makes it easy to do.

WOMAN:She will be completely healed in two weeks.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The morning after surgery, Van was still puffy and a bit groggy. But Orbis sent us this video taken a few days later, a child who, in Dr. O’Hara’s words, had symmetry restored to her life.This is Fred de Sam Lazaro for the PBS NewsHour in Hue, Vietnam.

JUDY WOODRUFF:And Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

The Flying Eye

Since 1982, the Orbis Flying Eye Hospital has traveled from country to country, performing surgeries and training local medical staff. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro meets up with the flying hospital in Vietnam.

First class seating

A 90-minute procedure was followed closely on video screens in the classroom on the plane. Using video links or even flying trainees to a California hospital may be more economical, Orbis says a key part of its mission is to raise awareness of eye disease, is often neglected amid myriad other challenges faced in developing nations.