JUDY WOODRUFF:Next: part two of our look at Rwanda 20 years after the genocide that left almost one million people dead.Since 1994, Rwanda has made progress in reducing extreme poverty. Health care has gotten special attention, with the help of a Boston-based organization.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has that story, part of his Agents for Change series.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Bosco Ntawugiruwe is a farmer who barely scraps by. He didn’t finish high school, but he is also a foot soldier in a public health army that’s delivering results as impressive as the view on his way to work in Rwanda’s remote volcanic highlands.

BOSCO NTAWUGIRUWE (through interpreter):Have you been taking your meds?

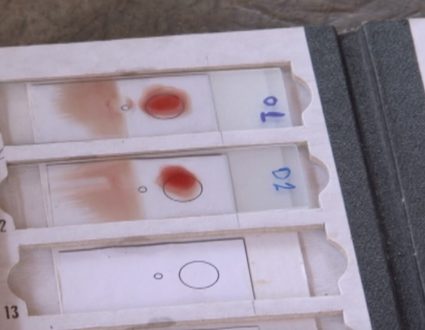

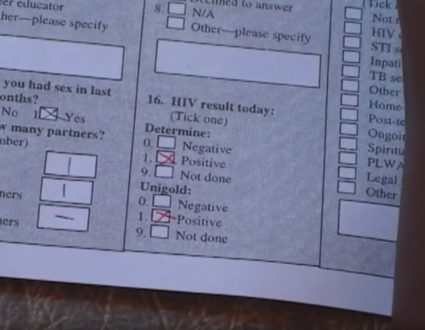

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Each day, he checks to make sure patients take their medicines for HIV, for tuberculosis, or checks on the recovery of a malnourished child.

BOSCO NTAWUGIRUWE (through interpreter):She’s looking good.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Average life expectancy has more than doubled in the past 20 years. It’s now 62; 99 percent of Rwandans have access to safe drinking water.And although this nation of 12 million remains poor, more than one million Rwandans have been brought out of poverty in recent years by one of Africa’s most robust economies.The transformation is striking for those with memories of the massacre of nearly one million people 20 years ago. After the genocide, this tiny, crowded country, one of the world’s poorest, was written off, including in one prominent medical journal, says Health Minister Dr. Agnes Binagwaho.

DR. AGNES BINAGWAHO, Minister of Health, Rwanda: Just after the genocide, there was an article published in The Lancet saying Rwanda is a land of desolation; don’t invest there.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Rwanda’s post-genocide government had little credibility early on, drawn mostly from an army of exiled rebels. It’s leader, Paul Kagame, consolidated power to become president and has been called everything from a benevolent to a ruthless dictator for cracking down on freedom of expression.He’s been accused of interference and plunder in his mineral-rich, but troubled neighbor, the Democratic Republic of Congo, where many of the genocide-era regime fled after they were defeated.But there’s no question Rwanda has changed, something that’s attracted initially reticent aid groups. One of them is Boston-based Partners in Health.Dr. Peter Drobac heads its Rwanda office.

DR. PETER DROBAC, Partners in Health: One of the things that I see Rwanda having done very effectively is really take ownership for its own development activities. What happens all too often in — in poor countries is that the agenda is driven by the donors or by the development agencies.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Despite meager resources, he says, Rwanda has built a new health care system. Rwanda has a severe shortage of doctors. There’s just one for every 100,000 people. The comparable figure in the U.S. is 273. So there’s a concerted effort to train other providers, nurses, and especially community health workers, who are volunteers. They go into their neighborhoods to look for early signs of disease and illness. Bosco Ntawugiruwe is one of 45,000 health workers. Elected by their communities, they receive six weeks of training in basic preventive health and periodic refresher courses.

BOSCO NTAWUGIRUWE (through interpreter):I always wanted to be a teacher, so this is very fulfilling. I have skills now and I am giving back to the community.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:When 1-year-old Francine began showing signs of illness, her mother first sought out her community health worker for advice.

WOMAN (through interpreter):It wasn’t hard to find Bosco. He advised me to grow a kitchen garden to grow more fruits and vegetables.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:He also took mother and child to the regional health center, where Francine was treated for malnutrition, one of many conditions that can be diagnosed and treated before they escalate, says Health Minister Binagwaho.

DR. AGNES BINAGWAHO:They can treat 80 percent of the burden of diseases at community level, especially for woman and children under 5, meaning cough and fever. They give antibiotic. Malaria, they do the diagnostic, and they do the treatment.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:As a result, the number of children dying before age 5 has dropped to a quarter of what it was in the year 2000. The number of mothers who die in childbirth is down 66 percent since 1990, in part because 99 percent of pregnant women receive at least one prenatal care visit.

DR. AGNES BINAGWAHO:We should demystify care-providing, provide — the way we provide care.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Demystify care, basically?

DR. AGNES BINAGWAHO:Yes, demystify. Yes, demystify. And we should — we should implore the community to be in charge.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Patients who need more attention go to regional health clinics staffed by nurses and, when needed, to hospital.The focus has been on the poorest and most isolated regions, unlike most countries, whose best facilities are in cities. Rwanda’s most modern hospital was built in Butaro, in the mountainous north, mostly with funds from Partners in Health.Emmanuel Kamanzi is a manager with the group.

EMMANUEL KAMANZI, Partners in Health: While we were building, people couldn’t believe this was their hospital. They are like, this is a resort coming up for the experts, for muzungu.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For white people, for the tourists.

EMMANUEL KAMANZI:For white people, for tourists.But we were like, look, this is your hospital; this is what you deserve.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The government runs this hospital with some operating money and expertise from Partners in Health. The goal is to build local capacity in the public sector, a lesson the group’s Dr. Drobac says it learned in Haiti, where it began working 27 years ago.

DR. PETER DROBAC:After the earthquake, for example, when billions of dollars were pledged for reconstruction for Haiti, almost none of that money went into the public sector. And it was because of impressions that the public sector is weak, is corrupt, is disorganized, is ineffective, but what happens is, you really get a self — self-fulfilling prophecy.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Rwanda’s public sector has won high marks for being largely free of corruption. It’s perhaps the only nation, Drobac says, where U.S. government aid for HIV/AIDS drugs goes directly to the government, because it is trusted.

DR. PETER DROBAC:Where, rather than all of the aid going through nongovernmental subcontractors, non-profits and for-profits that take 30, 40, 50 percent of the overhead and then implement programs, the money’s going directly to the government.

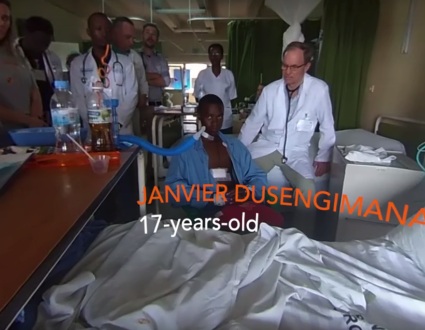

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The Butaro hospital is also part of an effort to look beyond infectious diseases, which have long dominated public health efforts in poor countries, to noncommunicable diseases.

DR. MPUNGA THARCISSE:Hypertension, cardiac failure, also diabetes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Hypertension, cardiac failure, also diabetes.

DR. MPUNGA THARCISSE:Diabetes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Medical director Dr. Mpunga Tharcisse says, in its first year of operation, the hospital has treated more than 1,500 cancer patients.This is the cancer ward?

DR. MPUNGA THARCISSE:This is the cancer ward.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:So this is the only place in Rwanda where patients without means, poor people, can actually get treatment for cancer? Is that fair to say?

DR. MPUNGA THARCISSE:Yes, that’s — that’s true.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For the first time, patients in a public hospital are able to receive chemotherapy. For now, the expensive drugs are paid for by Partners in Health. It means a new lease on life for patients like 4-year-old Yvette, being treated for kidney cancer, and for Bernadette, a 35-year-old mother of four who underwent a mastectomy for breast cancer.

WOMAN (through interpreter):It was very difficult then they first told me it was cancer, because, in my mind, cancer meant death. But the doctors were by my side. They kept telling me, things will be OK. I thought I was going to die after the operation. I had bad reaction to the medicine. I had pains in my chest. But now I’m living a new life.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The new life for cancer patients here might be a metaphor for post-genocide Rwanda, resurgent after a near-death experience with a long journey ahead.

GWEN IFILL:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

“I always wanted to be a teacher, so this is very fulfilling. I have skills now and I am giving back to the community.”

Bosco Ntawugiruwe, community health worker