FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Gudia and Babitha are sisters and they share a lot in common. Each is a mother of two young sons, both live in the same extended family home and they’re even married to brothers. With their husbands, they have far less in common: the young women come from hundreds of miles away, where dialect and diet are very different. How young are they? That’s a sensitive question.

GUDIA: (through translator) I’m 28 and she is 25 or 26.

DE SAM LAZARO: Neither woman went to school and may not actually know her age. But Yudhvir Zaildar, a Ph.D. student who studied the growing number of marriages like theirs, says women’s ages are exaggerated because it’s illegal to marry before age 18.

YUDHVIR ZAILDAR: (through translator) I would say in that case that both of them were under 18 at the time of marriage. And in such cases the husbands are often twice, sometimes three times their age.

DE SAM LAZARO: Their husbands told me they were 40 and 35. They’re caught in what demographers call a marriage squeeze.

There are no local women to marry, they said, and those who are eligible are taken by people of more means.

BRIJENDER: (through translator) We have no land, we have no steady job. That is the big problem.

DE SAM LAZARO: The northern farm states of Punjab and Haryana have a lopsided gender ratio. In some regions, particularly economically prosperous ones, there are as few as 650 female births for every 1000 males.

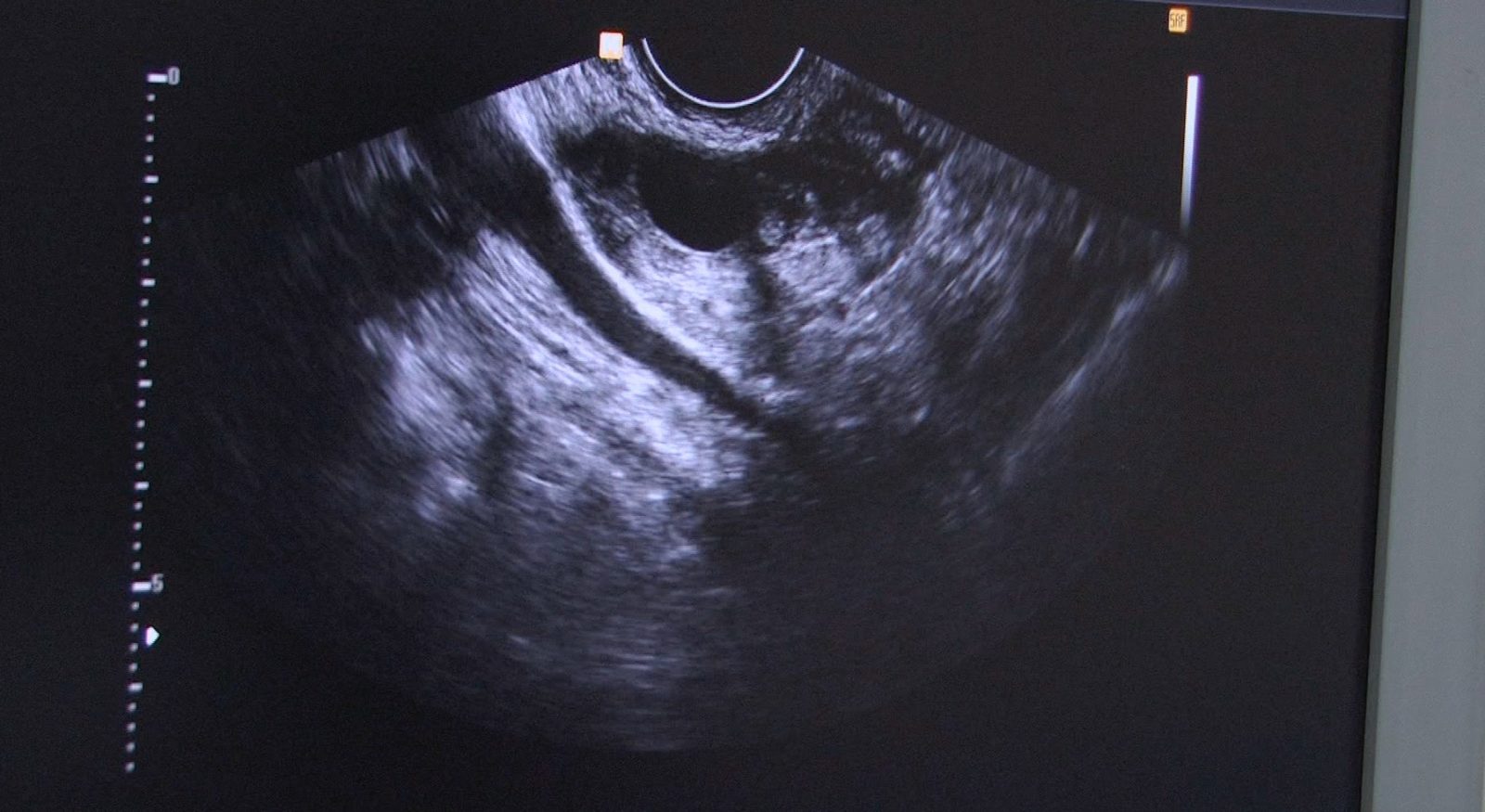

That’s because for at least two decades, ultrasound scanners have been used to detect the sex of fetuses and have led to widespread abortion of females. One generation later, it’s led to a shortage of brides in a culture where everyone is expected to marry.

PROF. RAVINDER KAUR (Indian Institute of Technology): 98 to 99% of Indian men and women do get married. So it is considered to be the socially honorable thing to do. It gives people social adulthood because there is no courting, there is no cohabiting before marriage and so how do you move on to the next stage of life?

DE SAM LAZARO: Men like Ramesh and Brijender find brides like Babitha and Gudia in impoverished parts of India. For their part these women say their own marital prospects were dim in eastern Bihar state where they grew up. Marriage has, literally, been a meal ticket.

GUDIA: (through translator) I know my husband is much older but then we were so poor, there was not enough food, not enough for simple clothing. Here we eat, we have everything. We didn’t have a refrigerator, cooler, fans, television.

DE SAM LAZARO: But marriage is not always what such women from other regions are led to believe.

The northern farm states, where India’s Green Revolution began in the 1970s, have a reputation in other parts of the country for abundant food and prosperity.

So, 20 year old Beena says, in the impoverished east where she’s from, it was not hard to convince her parents to consent to a marriage that would take her a thousand miles away.

BEENA: (through translator) They said it would be fancy, like life in a Hindi movie – big houses, things like that.

DE SAM LAZARO: And what did she find? Well, you can see for yourself, she said.

Beena’s parents also had a financial incentive: they didn’t have to come up with a dowry. She says they could never afford one anyway.

BEENA: (through translator) My family did not receive anything but they also gave nothing. The middleman got about 30 to 35,000 rupees, and the groom’s family paid for that.

DE SAM LAZARO: That’s about 500 dollars. Life can be lonesome at times, says Beena, who was married at 15 and now has two children. No one speaks her native Bengali and it took her time to adjust to the local diet and customs but she says she’s become reconciled to it.

BEENA: (through translator) I’m married now, this is just the way it is. It’s my fate.

DE SAM LAZARO: Visit any village here in the impoverished rural areas of Beena’s native Bengal and you’ll hear stories of missing young women, many of them minors.

SALEHA BIBI: (through translator) I prayed for my daughter in the mosque, and I gave sacrificial offerings, and I keep praying so I can find her.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s been ten years since Saleha Bibi heard from her daughter Manuara. She and husband Mazlum Momin were approached by a stranger proposing marriage to their daughter. They say she was 18 then. Momin says the supposed groom quickly slipped away with their daughter and was never heard from again.

MAZLUM MOMIN: (through translator) I went to the police, they said “Fine, but we need a photo of the girl first,” and we did not have a photo to give them.

DE SAM LAZARO: In any event, many people here say, the police are indifferent or worse in such cases.

JABANI ROY: (through translator) There’s no use in going to the police, they would simply accuse us of selling our daughter.

DE SAM LAZARO: In fact some people, like Jabani Roy, here with her son Bimal, do receive money.

ROY: (through translator) Two thousand rupees.

DE SAM LAZARO: Two thousand rupees, she said, about 40 dollars. It’s been years, and she’s never heard from her daughter.

ROY: (through translator) I think something bad happened.

BIMAL: (through translator) If she would have returned at least once we would feel better, that she was okay. But she hasn’t even returned once.

DE SAM LAZARO: Kailash Satyarti, one of India’s best-known anti-trafficking activists, says marriage is but one fate tens of thousands of young women face every year across India.

KAILASH SATYARTI (Sociologist): They are stolen, they are sold and resold and resold at different prices and eventually they end up as child prostitute, child slave, many of the missing girls from West Bengal and Orissa and Assam other northeastern state, they are found being married to old man in Punjab and Haryana and sometimes in Delhi. A 14 year old girl could have been married to a 40 year old man.

DE SAM LAZARO: Back in Haryana, elders in the village we visited say the root cause of the so-called imported brides phenomenom – the illegal practice of sex selective abortion – continues.

SRI RANBIT SINGH: (through translator) It goes on underground. It’s continuing.

JOGINDER SINGH: (through translator) In our society, the status of women is still low. It’s in the mindset of people. That needs to change. Otherwise how do we sustain a society?

DE SAM LAZARO: Sociologist Kaur says everyone knows it’s a problem for the larger society. The challenge is to change the mindset of individual families.

PROF. KAUR: They don’t connect the dots. They’re not seeing that, you know, eliminating their own daughters is leading to this bride shortage. So if, as long as they can get somebody from somewhere else, they think that’s okay.

DE SAM LAZARO: But ironically, experts say, the young sons of Gudia and Babitha may well face less of a bride shortage. Grad student Yudhvir Zaildar says it’s for unlikely reasons.

YUDHVIR ZAILDAR: (through translator) The reason is these wives who are brought in from outside, they make them pregnant as quickly as possible and produce many children so that they won’t run away.

DE SAM LAZARO: The young women may feel tricked or homesick but they are far less likely to run way if tied down with children or pregnant. And that means fewer abortions and more girl babies.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro.

Gender Imbalance

Sex selective abortion in India has lead to a bride shortage decades later that has created a market for wives from across India.

Ultrasound scanners used to detect the sex of fetuses have led to widespread abortion of females. One generation later, it’s led to a shortage of brides in a culture where everyone is expected to marry.