FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Jains have often been confused with and even counted in census surveys as Hindus. While there are fundamental similarities, like the belief in rebirth after death, Jainism is a distinct belief system dating back at least to the sixth century BC. Its numbers declined as ancient rulers who supported Jainism faded into history and India fell under new conquests. Today there are only about five million Jains in a country of 1.2 billion. But Jainism’s imprint on Indian history is large, including-profoundly-India’s independence movement.

PROFESSOR JAMES LAINE (Religious Studies, Macalester College): When we think about the notion of ahimsa or nonviolence that is central to Gandhi’s thought, you know, that goes back to Jain teachings and is very, very central. It’s probably the most important doctrine that they uphold.

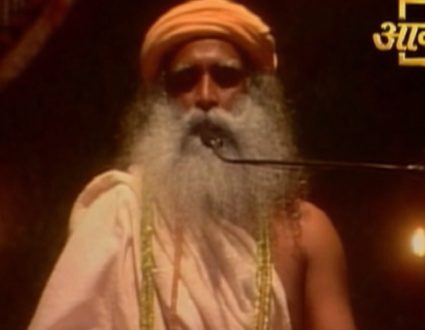

DE SAM LAZARO: Mahatma Gandhi was Hindu, not Jain. But his approach-nonviolent resistance to British rulers, his shunning of most material possessions, and celibacy-are key Jain teachings, as is truthfulness. Stealing is prohibited. Jainism’s strictest followers-monks like Pulak Sagar-take these teachings to the absolute extreme, renouncing even clothing. His routine of prayer and meditation begins each day at 4:00 am, interrupted by one daily meal at around 10:00 am.

MUNI PULAK SAGAR: (through translator) We don’t eat off plates or use any utensils. We eat with our hands. After the meal and until about 3:00 pm, a period of meditation follows, after which we receive people.

DE SAM LAZARO: Monks or gurus are revered for adopting the ways of Jainism’s ancient teachers. The last and most influential of these was Mahavira, the son of a powerful king who lived in the sixth century BC. Today, there are about 1,300 monks and nuns. Unlike male religious, nuns cover themselves with simple white garments. Sagar is 41, a college graduate who came from a well-to-do family. He became a monk at 23, inspired on a visit to a Jain guru by the peace and contentment that he says comes through liberation from bodily and material want.

MUNI PULAK SAGAR: (through translator) We have to always keep this in mind: that the things we’ve collected we have to leave behind. We can acquire all the diamonds and jewels in the world, but the shroud of a dead person has no pockets. You can’t take these things with you.

DE SAM LAZARO: Ironically, Jains are well-known for their wealth and business success, particularly in the jewelry business. In contrast to the ascetic lifestyle of monks and nuns, Jain temples are grand edifices. There’s even one in Antwerp, Belgium, the world’s diamond-trading capital. But ostentation rarely extends to the lay Jain lifestyle.

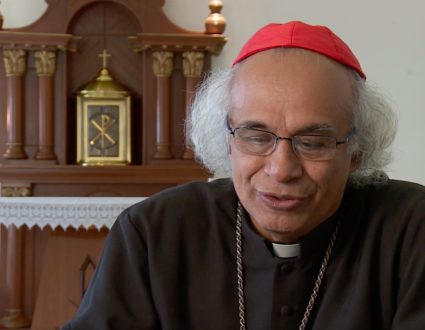

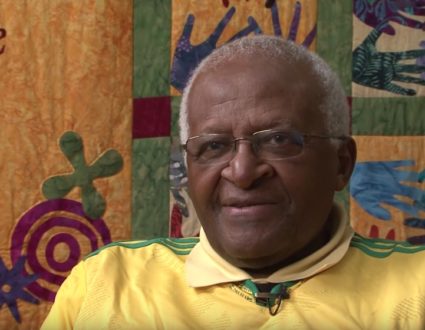

Professor James Laine

LAINE: There are a lot of people who are quite wealthy, quite successful but they take from the ascetic ideal just enough to give them the kind of self-discipline and work ethic that ultimately also helps in their business, and then they have the sense of it’s my responsibility as a wealthy person not to simply indulge in my own pleasures but to also make gifts back to the religious community to support those heroic figures who are going to go the whole way and wear just a piece of cloth or nothing and fast all the time.

DE SAM LAZARO: Mahavir Parshad Jain is a third-generation jeweler in Delhi. His three sons also run the business. And three generations of the family share a large home in India’s joint family tradition. They are very well-to-do by India’s standards, but insist their lives are simple and devoid of excess.

MAHAVIR PARSHAD JAIN (Family Patriarch): (through translator) We earn our money by ethical, humane means. We avoid wealth that would be acquired by cheating others or by any violent means, and we only accumulate that which we need. I have just one store. We’ve had it for the past 65 years, and that is how we feed our family.

SHOBHA RANI JAIN (Family Matriarch): (through translator) We never eat outside. All our food is cooked in the home, and we only eat from about 20 vegetables.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Jain diet is informed by the call for nonviolence toward all life, animal and plant. So it’s not just vegetarian, but also forbids plants that grow below ground, like onions or potatoes, since extracting them kills the whole plant and might also hurt insects and worms. In the Jain home-and Jain is a common surname-the grandparents avoid eating after sundown. They keep a daily regimen of prayer rituals at temple, and they provide food for monks. They also took a vow of celibacy eight years ago.

RAJIV JAIN (Son): Jainism-the foremost thing is to have control on your willpower, on your thoughts.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s asceticism on a kind of sliding scale, informed by one’s circumstances.

GEETIKA JAIN (Granddaughter): The high ideals and a lot of other things that our grandparents follow-it is very difficult for the present generation.

DE SAM LAZARO: Twenty-year-old Geetika Jain who attends university says she has no difficulty resisting smoking and drinking. But living in a modern world demands more flexibility.

GEETIKA JAIN: My grandparents said they don’t eat food at night. But going out with friends, having a social circle and having to maintain those social circles, we sometimes-we can’t be as strict as our grandparents. So we won’t eat food at night when we’re at home. But when we have to go to a social gathering or marriage or something like that, we take a side-step and we follow what socially we are able to do.

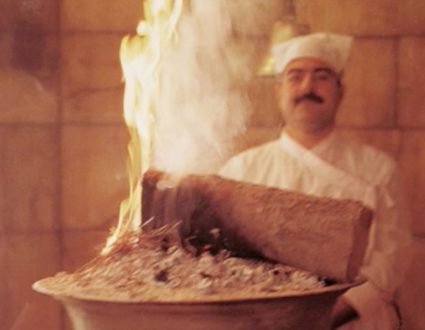

DE SAM LAZARO: That flexibility to “take a side-step,” to choose one’s individual pace, may be traced back to Jainism’s early days. Twenty-five-hundred years ago Jainism thrived here. It was the dawn of long-distance trade that opened people to new goods and new ideas, and this appealed to the rulers and traders of the day. They had long been bound by the dogma and scriptural interpretation of Hindu priests.

LAINE: They simply broke with religious orthodoxy. They said we’re not going to rely upon scriptures; we’re going to analyze the world as we see it. And their analysis of the world came down to the idea that your rebirth in this world, the karma that you accumulate comes from the violence that you do to the world. And so our ultimate freedom will be the result of our reduction of that violence to an absolute.

GEETIKA JAIN: Harming another being-that’s what my idea of what violence is.

DE SAM LAZARO: Preventing violence can involve wearing a mask to guard against accidentally swallowing a flying insect. So can proper diet and ethical business dealings. Such actions wipe the soul of harmful karma, bringing one closer to god and liberation from the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. It might take more cycles of rebirth to achieve that liberation. Until then, Jains are asked to support monks like Pulak Sagar, who are much farther along in that path.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Delhi.

Jainism

How Jainism, a distinct belief system dating back at least to the sixth century BC., has left its imprint on modern India.

A Path of Non-Violence

Influential Beliefs

Mahatma Gandhi was Hindu, not Jain. But his approach-nonviolent resistance to British rulers, his shunning of most material possessions, and celibacy-are key Jain teachings, as is truthfulness. Even the Jain diet is informed by the call for nonviolence toward all life, animal and plant. So it’s not just vegetarian, but also forbids plants that grow below ground, like onions or potatoes, since extracting them kills the whole plant and might also hurt insects and worms.