Judy Woodruff:They are lethal legacies of war. Land mines present a constant hidden threat.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Cambodia, where the danger is part of daily life. But an unlikely battalion of animals is making a difference.This is part of Fred’s series Agents for Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Let’s face it, rodents rarely trigger warm fuzzy feelings in most people.But these African giant pouched rats, being gently awoken from their cages, are called hero rats by their handlers. They have names like Harry Potter, Godiva, and Frederick — no relation.After getting sunscreened up, this rat pack of 11 animals is headed out before dawn to a former battlefield in rural Cambodia. Their task? Sniff out land mines.

Mark Shukuru:Everyone was surprised, even me, when I heard that the rats also were detecting land mines. It was like something unbelievable to me.

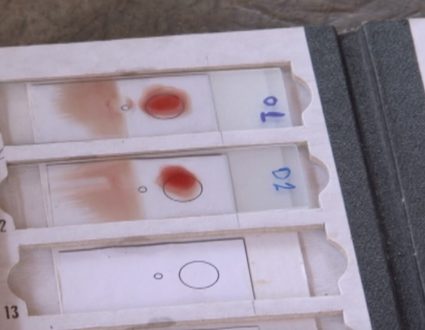

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Mark Shukuru is head rat trainer in Cambodia for the Belgian non-profit APOPO. He is from Tanzania, where this species is also native, and he learned early that they have some of the most sensitive noses in the animal kingdom.Each comes out of a rigorous program in Tanzania that trains them to distinguish explosives from other scents. Each time they sniff out TNT buried in this test field, a trainer uses a clicker to make a distinct sound, and they get a treat.

Mark Shukuru:So, TNT smell, clicker, food. TNT smell, clicker, food. TNT smell, clicker, food.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The drill can take up to 12 months before handlers are confident that, when the animal scratches in place, an explosive is buried below.

Mark Shukuru:We have never missed anything with the rats. So they’re doing good.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Rats have a number of advantages compared to human de-miners, who must rely on metal detectors. They detect a lot of scrap metal. These are, after all, old battlefields. They are litter, but they don’t always contain explosives, whereas these guys are trained to sniff out TNT, which is the explosive in most mines.Since 2016, APOPO’s hero rats have found roughly 500 anti-personnel mines and more than 350 unexploded bombs in Cambodia. They’re the second animal to be deployed in mine clearance. Dogs were first. Animals can work much faster than humans, although, when the land is densely mined, metal detectors are considered more efficient.Thuch Ly who leads the government’s de-mining effort, says there’s plenty of work to go around. The ministry has exhaustive maps of areas it calls contaminated.

Thuch Ly:We come out with the numbers that are around four to six million anti-personnel land mines in this country, so we still have a long way to go.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:That translates to a lot of contaminated land in this largely rural agrarian country, an economic and existential threat.

Thuch Ly:We have more than 26,000 people killed and injured over the years; 30 percent of them are women and children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s the legacy of three decades of conflict that ended in the late ’90s. In Cambodia’s west, land mines were buried by the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and by the Vietnamese army that drove them from power, alongside the new Cambodian army.In the east, near Vietnam, lie millions of tons of unexploded American bombs dropped during the war.

Aki Ra:We hold like this. Be careful. Then press on top here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:This may be the only country with a land mine museum. It was started by Aki Ra, who was conscripted as a child to fight for the Khmer Rouge.

Aki Ra:We cut the wire.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He laid mines himself, and has spent much of his adult life trying to remove them. He disarmed many of the devices on display here, and says his goal is to raise awareness of what mines can do.

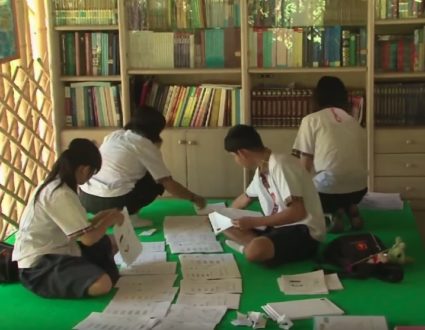

Aki Ra (through translator):The children during my time all went through it, but it seems like the young, the children growing up during this generation, they’re not aware of the danger or the casualties of land mines that still occur today in Cambodia.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Tens of thousands of Cambodians live in close proximity to the dormant killers. This school was just steps from the mine field we visited with the APOPO rats.

Rebecca Letven:People are forced to enter these contaminated areas quite simply because they don’t have a choice, because their livelihoods depend on it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Rebecca Letven works with the British Mines Advisory Group, one of several aid agencies working in Cambodia; 27 years into the collective effort, they have freed up some 18,000 acres. That’s less than a 10th of the terrain considered contaminated.

Rebecca Letven:It’s important that we don’t forget what happened here in Cambodia, and we don’t forget that the country itself is still very heavily contaminated.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:This year’s toll so far, 11 killed and 51 injured. At this regional prosthesis hospital, a steady stream of victims arrives each day to be fitted or refitted with artificial limbs.

Sna Him (through translator):The old one was getting really tight, especially around my thigh.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Thirty-nine-year-old Sna Him stepped on a land mine in 2002. Like many patients here, he’s a small farmer, growing rubber and cashew nuts with his wife and three children.

Sna Him (through translator):I am always very careful when I walk in the fields, because I am worried that it could happen to my other leg. I feel very upset that I lost a part of my body, because it prevents me from doing other activities that normal people are able to do.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Meanwhile, the various de-mining teams continue to inch forward with the tedious, dangerous work. There’s little evidence anymore of the hostility that drove the shattering conflict. Old combatants have moved on over time, but, Minister Thuch laments, so has the world’s attention.

Thuch Ly:I think there’s a moral obligation for everybody involved in war in the past. I think that it was the Cold War and then small nations like Cambodia been victims of this.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:APOPO plans to bring in some 40 more rats to expand the force and replace retirees. Each animal works about eight years, and then lives out the rest of its days alongside fellow heroes, all working toward the day when they can broadcast to the world that Cambodia has destroyed the last unexploded bomb.Its big task is to convince enough donors to help with the cause.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro near Battambang, Cambodia.

Land mines

Giant African pouch rats have become unlikely allies in the fight to clear the millions of landmines that remain decades after the war in Cambodia ended.

Cambodia