REV. COLUMBA STEWART, director, Hill Museum, St. John’s Abbey: Who would have thought that in a monastery in Central Minnesota is the world’s largest collection of photographs and manuscripts?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For 50 years, this underground library at St. John’s Abbey has collected and catalogued historic Christian manuscripts. Father Columba Stewart says it’s part of a monastic tradition that dates back to the 6th century.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: I’m a Benedictine monk. There’s an impulse in Benedictines to exercise this role of cultural guardianship. And that’s an impulse that continues even in the modern age.

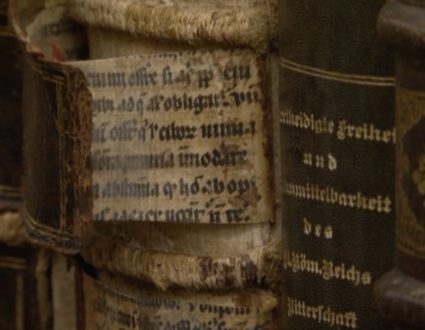

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Many of the texts were handwritten long before printing presses. Some, like this Koran, were created soon after, this one commissioned for study by some of the first Protestant scholars.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: It’s the first printed copy of the Koran. It was published in 1543, with a preface by Martin Luther.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Father Columba says these ancient texts echo with relevance to our time.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: Christians were — were dealing with Islam and there was a real desire to understand it better. So the result was they wanted a translation of the Koran into Latin, so that Christians could read it. And, of course, it wasn’t for the sake of religious understanding, it was for the sake of refutation.

And this whole question of how Western, predominantly Christian countries, dialog with or relate to majority of Muslim countries is something we’ve been talking about since 9/11. But what we forget is there are centuries — centuries of experience of Christians and Muslims

And in many of these areas, significant Jewish communities as well –living together. And it wasn’t always easy. And these manuscripts tell the story of that. They tell the story of legal prescriptions, which were made either to protect or to oppress a particular community.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Preserving that history is a matter of utmost importance to religion scholars like Father Columba.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: If you believe that we can learn from the past — the past of our lives, the past of our families and our own nation or culture, the only way the past has come down to us is in the form of these writings.

Ethiopian manuscript, Latin manuscript.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Impressive as the physical manuscripts are, this library’s much larger collection consists of digital copies of sacred texts. Most of the originals remain in churches a world away from here.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: Over 100,000 manuscripts from Europe, the Middle East, from Ethiopia, from India; well over 30 or 40 million pages. We’ve lost count long ago.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The texts are recorded digitally, catalogued

and stored in underground vaults.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: And our pledge is that those will be safe forever.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The library’s effort began in the 1960s in Europe, a time when microfilm first became available; also a time when there was fear of a nuclear war.

Next, the librarians went to Ethiopia, anticipating, correctly, that many of that country’s orthodox manuscripts could be destroyed in the political turmoil of the ’70s and ’80s.

In recent years, the focus has been on the Middle East.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: Our goal since 2003 was to do as many Eastern Christian manuscripts in the Middle East as possible, because we all know that these manuscripts are endangered from a variety of causes.

The one people think of most is violence, because they associate this region, whether it’s Lebanon or a place like Jerusalem, certainly a place like Iraq, with immediate physical danger to manuscripts.

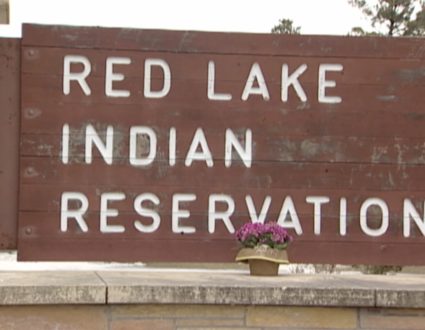

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: We followed Father Columba to Jerusalem, a city fought over for centuries among Muslims, Jews and Christians; also among Christians.

These pilgrims were on their way to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, where they believe Christ was buried.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: I’m going to show you a diagram of the Holy Sepulcher Church. All that’s left now is really this area.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The building was destroyed by Muslim rulers and rebuilt in the 13th century by the Crusaders. It is one of Christianity’s holiest sites; also a symbol of its divided family, something that complicates the task of tracking down and digitizing their sacred books.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: So the Greeks have the central piece, the Armenians have quite a bit of the chapel surrounding the center, the Latins have the far side, the Syrians have a small chapel in the back, the Copts have a small chapel inside. So it’s a little microcosm of all the different religious traditions here in the Middle East.

And, unfortunately, relations are not always easy, because when you have all of these different groups living in a — what is a fairly small building, they’re fiercely protective of their rights.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Many regions where these traditions evolved, modern day Turkey and Iraq, Armenia and Russia to the north, as far south as India, have seen war and upheaval through the ages. And just

last October, a Syriac Orthodox Church was bombed in Iraq. All this increases the urgency to record the texts that have survived, says

Father Columba. He is particularly interested in digitizing the Syriac church’s collection in Jerusalem.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Father Columba.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: How are you?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Fine. Thank you very much.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: Good to see you.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It will take dogged diplomacy.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: These Eastern Christian communities, many of which have been persecuted — massacres are within living memory –this stuff is really in their gut.

And so you — you have to build a relationship where they understand that the motives that we bring to these projects is one of deep reverence.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Minnesota library also brings the money need for such projects, several hundred thousand dollars each year, raised from various private donors. Local church staff are trained in the tasks. And while copies go to Minnesota, the local church retains copyright.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: So if you have a monk or a layperson who you think would be a good person to do this work or two people.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: And our monks, always, they will be with them. Yes.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: This is a very — a very old manuscript, perhaps 7th, 8th century?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It doesn’t say.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: It doesn’t say.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It doesn’t…

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: But it’s very old…

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In years ahead, Father Columba expects to return repeatedly to the Middle East, until, as it were, the word is made safe.

Monastery Works to Preserve Ancient Texts

For 50 years, this underground library at St. John’s Abbey has collected and catalogued historic Christian manuscripts. Father Columba Stewart says it’s part of a monastic tradition that dates back to the 6th century.