Judy Woodruff:The number of coronavirus cases in India appears for the moment to have peaked, with a decline in daily infections in recent weeks.However, India’s economy, the world’s fifth largest, has yet to recover from a steep decline, compounding the suffering of millions of its poorest citizens.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has an update.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s a typical morning at Delhi’s main bus depot, thousands of migrant laborers returning from their rural homes, hoping to regain jobs they abruptly lost in March, when India went into a total lockdown.Thirty-eight-year-old Netrapal Yadav used to drive for a taxi company, work that helped support his wife, four children and elderly parents in their village about 150 miles away.

Netrapal Yadav (through translator):When the lockdown happened, I went back, but there’s no work there. It’s been very hard. I have had to take on nearly 35,000 rupees in debt. So I came back to Delhi. So now I’m going to see my old boss.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Worried about debts that total about 500 U.S. dollars, he decided to skip the rickshaw ride to his old workplace. The $3 fare is about what he used to earn in a full day.

Radhicka Kapoor:A lot of urban migrant workers were largely in the informal economy.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:I reached Delhi-based economist Radhicka Kapoor.

Radhicka Kapoor:They went back to the security of their villages, where they were sure that they wouldn’t actually starve. Essentially, there was a lot of rural distress even before COVID-19 struck. And now that has just got exacerbated.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:With the economy cratering, most recently at an annual rate of 24 percent, the government began easing its lockdown in May, despite falling far short of the goal of flattening the curve of COVID infections.So, laborers are back in the cities. Anxiously, they wait each day for work, but the cities are not back to normal, as Yadav would soon find out when he arrived at his boss’ place.

Harinder Singh (through translator):I just have no work. Right in front of you, there used to be 10 cars. Now I have only two. I got rid of eight of them.

Netrapal Yadav (through translator):Tell me, how am I going to feed my children? Where am I going to get bread for them? They go full days being hungry. It’s for their sake that I came to you.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The best that the boss, Harinder Singh, could provide was a cot in his open air taxi stand.

Harinder Singh (through translator):People are using their own personal cars. No one is using taxis.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:They’re also simply not going many places. Delhi’s once-thriving middle-class shopping centers sit nearly empty.

Radhicka Kapoor:So, it’s somewhat leading to a chicken-and-egg program. Businesses will invest only if there is demand, but, at the same time, vast majorities don’t have jobs.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And that’s unlikely to change soon, says Professor Ramanan Laxminarayan, who divides his time between India and Princeton University.

Ramanan Laxminarayan:It’s going to take probably years for the economy to climb back, because a lot of small businesses, medium enterprises have all been wiped out. And it takes time for that whole cycle of borrowing money, setting up an enterprise and then being able to make things happen.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Small and medium enterprises employ more than 90 percent of India’s urban work force, large numbers of them rural migrants. Some critics place blame their abject suffering on the government’s hasty, abrupt lockdown.But supporters say the country had to buy time to build testing capacity, supplies of protective equipment, and temporary isolation and care centers, like this one in a Delhi athletics complex.So far, this facility has never hit its 500-bed capacity.Dr. Rajat Jain, a volunteer physician here, has one troubling explanation.

Rajat Jain:The stigma is definitely a very, very big challenges, a lot of people who are scared of getting themselves tested.And that’s a pretty big challenge, because if they are not getting themselves tested and they are not aware, they are the one who are spreading the disease.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Some scientists say the actual number of infections is possibly three to four times the official total of about 8.6 six million. The official death toll is 128,000.

Ramanan Laxminarayan:The disease is pretty much uncontrolled at this point in time. It’s spreading from the urban areas, which have better testing. It’s spreading into the rural areas, which really don’t have health facilities to take care of patients.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Through all this, polls show Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains widely popular.

Ramanan Laxminarayan:What was positive about the Indian response was that there was never an attempt to sweep COVID under the carpet and say, this is not serious, as we saw in many other countries, like Mexico, in Brazil, and certainly the United States as well. That did not happen in India.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:But the prospect of sustained stagnation in a once-fast-growing economy is a worry. Half of India’s population is below the age of 25.

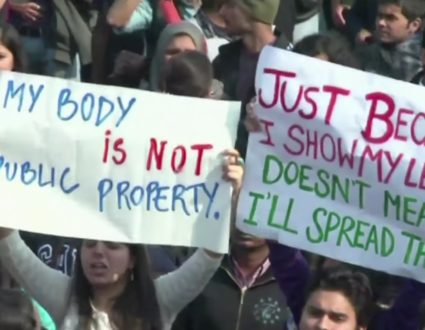

Ramanan Laxminarayan:The risk of social upheaval has certainly gone up.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Meantime, with Netrapal Yadav at the taxi stand…

Netrapal Yadav (through translator):I went to three, four different taxi owners, didn’t get any work. I might as well go back to the village. The boss is giving me 100 rupees to wash the cars, but I can probably make that at home.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Washing cars for $1.50, surviving on ramen noodles, he decided his third night in this makeshift sleeping arrangement would be his last. He spent his next night on the bus home.For the “PBS NewsHour,” with Rakesh Nagar in Delhi, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Judy Woodruff:Thank you, Fred. And Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

One crisis leads to another

With 1.3 billion people and the world’s fifth largest economy, the stakes are high as India fights both COVID-19 and a cratering economy. Small and medium enterprises employ more than 90 percent of India’s urban workforce, and a large number of them are rural migrants. After retreating to villages during initial lockdowns, workers are returning to cities—but their jobs haven’t come back yet.

“When the lockdown happened, I went back, but there’s no work there. It’s been very hard. I have had to take on nearly 35,000 rupees in debt. So I came back to Delhi. So now I’m going to see my old boss.”

“So, it’s somewhat leading to a chicken-and-egg program. Businesses will invest only if there is demand, but, at the same time, vast majorities don’t have jobs.”

“It’s going to take probably years for the economy to climb back, because a lot of small businesses, medium enterprises have all been wiped out.”