Judy Woodruff:A new study from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control shows that measles cases in 2019 reached their highest number in 23 years. Health officials blame the rise on a significant drop in vaccination rates.We may soon see other preventable diseases spike too. Childhood immunization rates have dropped sharply during the pandemic.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro began reporting today’s story early this year, focusing on one group working to improve child health in Pakistan.It’s part of Fred’s series Agents For Change. And a warning: Some viewers may find graphic images in this segment unsettling.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:We filmed these images just before the pandemic outside a Karachi public hospital one typical morning, where hundreds of people waited for hours just to see a doctor.Months into the pandemic, the throngs are still lining up, many people not wearing masks. Despite that, the virus seems to be under control in Pakistan.

Ahson Rabbani:Pakistan has been very lucky that COVID has not been devastated it like most other countries, and the jury’s still out on why we have been lucky.

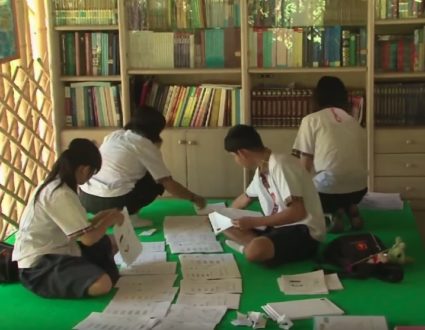

Fred de Sam Lazaro:I reached Ahson Rabbani on his phone recently. Back in January, we’d visited a project he leads in hospitals across Pakistan that’s aimed at reducing the country’s high infant mortality rate.After a spike in COVID infections in June, public health experts credit targeted localized lockdowns and luck for helping flatten the curve in Pakistan, a crowded nation of 220 million. That’s been a huge relief in an underfunded, overwhelmed public health system.Rabbani heads the ChildLife Foundation, started seven years ago by a group of business leaders who stepped in to help the decrepit public hospitals deal with emergency care for young children. One of every 20 Pakistani children doesn’t make it to age 5. The vast majority die before their first birthday.

Ahson Rabbani:These children are not dying because of pneumonia or diarrhea. These children are dying because a society has yet to decide that their lives are worth saving.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He says pneumonia and diarrhea are treatable and preventable through better hygiene and immunization. But it’s public indifference that allows them to claim hundreds of thousands of children’s lives every year in Pakistan.

Ahson Rabbani:I will tell you what’s the most difficult part when I go to E.R., the wailing of mothers. I mean, it shakes you when you see a mother in pain.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:On the front lines are staff of the neonatal intensive care unit, the nurse who disconnects life support from an infant who didn’t make it, the doctor who must disclose this to an exhausted mother.Daunting as the images are, the recovery rate has greatly improved since ChildLife set up this pediatric emergency room, particularly among the most critical patients.

Ahson Rabbani:The survival rate was less than 20 percent. Now it has quadrupled to 90 percent-plus. And it happens because of training, availability of doctors, systems, medicines, and a second doctor’s opinion through telemedicine.

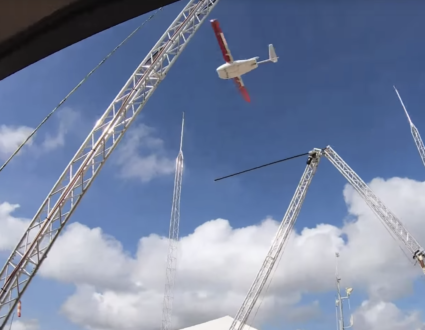

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Cameras in every resuscitation unit are connected to doctors in this virtual exam room. They work 24/7 with front-line providers across ChildLife’s network of hospitals.The pandemic has added stress and expense, things like personal protective gear and Plexiglas separators in the cramped neonatal intensive care unit, and ChildLife’s staff had its own COVID issues.

Ahson Rabbani:We had 28 people on staff who contracted COVID. But the show went on.

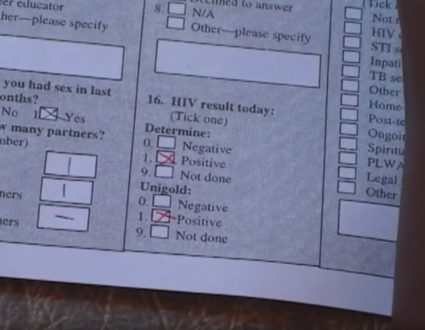

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Fortunately, all the staffers recovered. While Pakistan overall has been spared, there’s fear the pandemic has made children more vulnerable to easily treatable infections that come from the conditions so many live in. Immunization rates were already low in Pakistan, and they have dropped 25 percent during the pandemic.

Ahson Rabbani:That’s a very real risk, especially for things like Typhoid and measles and even polio.And WHO fears that we may have gone back a couple of years to get back to the same level of immunizations.

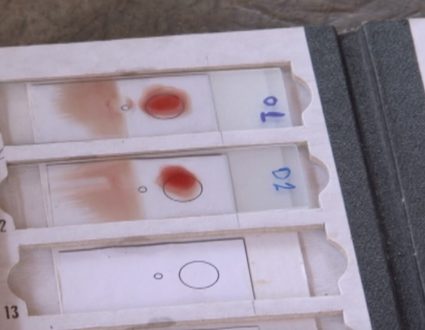

Fred de Sam Lazaro:That could mean more patients like this 7-year-old boy brought in during our earlier visit, unconscious and shivering uncontrollably.Doctors suspected it was meningitis, something that’s easily prevented with a vaccine that’s recommended in infancy in developing countries. Two injections in quick succession stabilize his condition.For Dr. Zareen Qasmi, the next challenge was to coax his parents to consent to a spinal tap, extracting a sample of spinal fluid to confirm the diagnosis and inform future treatments.They listen and ask to have a family consult.

Zareen Qasmi:After 10 minutes, he came back and said, no, sorry, we are not allowing you.

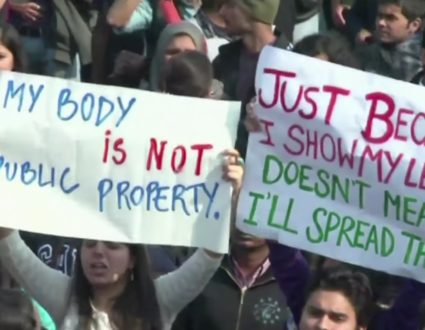

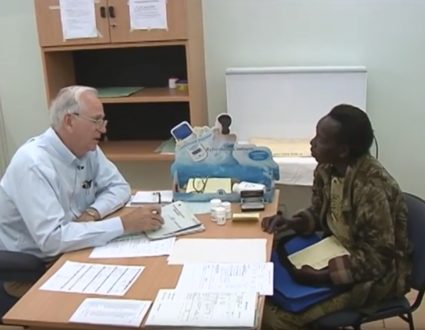

Fred de Sam Lazaro:They’d heard of a case where a spinal tap was fatal, they told her. Their decision could put the boy at risk for a range of future complications.The problem is not just the parents’ lack of education.It basically boils down to trust.

Zareen Qasmi:Exactly.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And a lot of patients here don’t trust the system.

Zareen Qasmi:Yes.

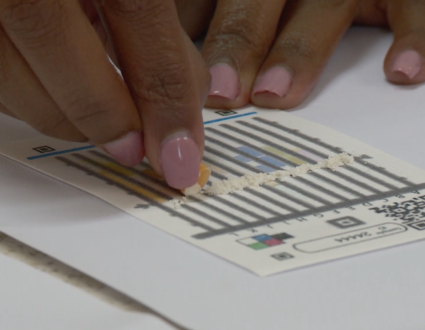

Fred de Sam Lazaro:ChildLife tries to build that trust by building relationships beyond the emergency visit. Parents’ phone numbers are recorded when they come in, so text reminders can be sent when the children need shots, particularly important now with the pandemic.On our pre-pandemic visit, Fatima Zulfiqar told us her four children are up to date on their shots. Still, she recently had to rush her then-7-month-old Khadija into the emergency room with acute diarrhea and vomiting. The problem is not poor hygiene, she says, but poverty itself.

Fatima Zulfiqar (through translator):We have four families that share this space. It’s hard to maintain cleanliness and hygiene. She’s a child. She’s small. She crawls around, picks up stuff, puts it in her mouth. Life is very tough. We have got nothing.

Ahson Rabbani:If you live in a lane which has 20 houses, and every third house had a child under 5 die, you believe that children die. So, if you reduce infant mortality through preventive measures, through curative measures, people will have fewer children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:There’s hardly a higher priority, he says, in what is already the world’s fifth most-populous nation.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

The ChildLife Foundation

ChildLife tries to build trust in health care systems by building relationships beyond the emergency visit. Parents’ phone numbers are recorded when they come in, so text reminders can be sent when the children need shots, particularly important now with the pandemic.