William Brangham:The sharp rise in home prices across the country continues to hurt first-time homebuyers. It is widening an already large disparity in homeownership between white Americans and people of color, particularly African Americans.Nowhere is this gap wider than in the twin cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, part of our series Race Matters and Fred’s series Agents For Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s been a heavy lift that took years. But, last month, Tim Luckett crossed the threshold into a new home, a first step toward happily ever after with wife Melva and 6-month-old Melani.

Tim Luckett:Feels great to finally become homeowners.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Why did you want to own a home?

Melva Luckett:We wanted to be able to have her be able to play outside, have a yard, be able to take her out in the backyard, play outside in the front, and have a home for her.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:She wants to be on that yard right now.

Melva Luckett:Yes, she does.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The Lucketts nabbed this modest North Minneapolis duplex against tall odds. There’s a severe shortage of homes, which has driven prices to record highs, and history has long stacked the deck against Black homeownership across America, and in this market in particular.

Kirsten Delegard:Racial covenants did the work of Jim Crow in the North, all over the North.

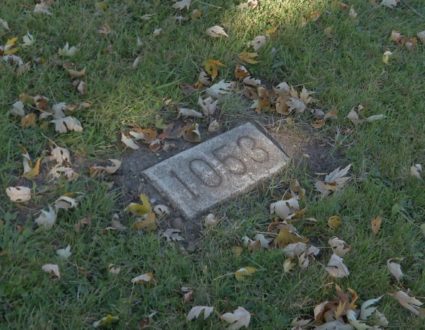

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For much of the 20th century, it was common to see provisions in Twin Cities real estate deeds that prohibited property sales to people of color.The practice was the subject of the 2019 Twin Cities PBS documentary “Jim Crow of the North.” It featured historian Kirsten Delegard, who leads the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice Project.

Kirsten Delegard:If you’re told all the time that the influx — that’s the language that was used — the influx of a person who was not white into your neighborhood would bring down your property value, that that was a real source of anxiety for individual people who maybe did not see themselves as racist.

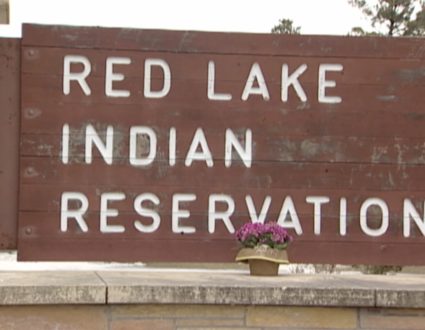

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Explicitly, such covenants are now illegal. But they have left lasting scars.Just 25 percent of Black residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul own their homes, a rate that’s well below the national average, and notable because this is considered one of the most affordable metropolitan areas in the whole country, if you’re white.About 75 percent of white residents here are homeowners. The disparity has had consequences. According to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, the median net worth of white households in Minnesota is $211,000. That same number for the state’s Black households is zero.

Jennifer Ho:The way that we accumulate wealth in America is largely through our homes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Jennifer Ho is Minnesota’s housing commissioner.

Jennifer Ho:If you weren’t allowed to buy in more affluent neighborhoods, if you weren’t given preferential pricing on your mortgage, if you bought a home and you had it taken away through eminent domain to build a freeway, you have been disadvantaged over and over and over.And so it is going to require decades of intentional work in order to bring that number back up, and bring it up so that it’s on par with white homeownership here in Minnesota.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:That’s the aim at Project for Pride in Living, or PPL, where Catrice Williams helps clients build credit and develop both job and financial skills that she says middle-class people take for granted.

Catrice Williams:In white communities, investments and owning land and real estate and all of these wealth creation tools and the knowledge around wealth creation, they have had access to since the beginning of time.What happens with African Americans and money is, like, we have been operating so long from a place of scarcity that, when we get access to it, it’s like, now I want to look affluent. And we don’t necessarily have the foundational knowledge of what it takes to sustain that affluence or create that affluence. So, we go with the next best thing, the look of it.

Lilricka Barber:I would get paid on Friday and be broke on Saturday.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:PPL has helped 39-year-old Lilricka Barber on her long journey to financial stability.

Lilricka Barber:I was on food stamps before. I was homeless before. I was on drugs before. I was in an abusive relationship before. But me being homeless really made me realize, who’s going to take care of my son?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Today, Barber actually works as a counselor for PPL and earns extra income selling custom-made clothes online. She has learned to practice extreme thrift.

Lilricka Barber:No impulsive purchases. Going to the food shelves at times when means was low, cutting my son’s hair, doing my own hair.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Was that a radical shift for you?

Lilricka Barber:Yes. Yes, it was.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For years, they have lived in a two-bedroom rental apartment that’s cramped, but the stability has helped Barber’s 11-year-old son, Malik, thrive in school in suburban Burnsville, Minnesota.Together, they set their sights on owning their own home.

Lilricka Barber:I love hosting and cooking for my family, so having a nice-sized backyard.

Malik Barber:My own area to play around in, and two bathrooms, instead of just one. And I do want a dog.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Last year, Barber was approved for a mortgage, an achievement that has since hit the brick wall of market reality.You have looked at how many properties, did you say?

Lilricka Barber:Over 200.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s been a roller-coaster ride, she says, that has led nowhere.

Lilricka Barber:I get all excited. I show my son. He visualized, OK, this is my room, I’m going to put my bed here, I’m going to put my dresser here. Yes, my dog, that can be his little spot.We put the offer in, and we don’t get it, because someone has come in and offered a cash offer.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Among the reasons for a shortage of affordable homes, investors have flipped many of them to rentals in recent years. And single-family zoning laws have prevented the construction of modest or multi-family dwellings, like duplexes and apartment complexes.Last year, Minneapolis became the first major U.S. city to ban such laws. As for the Lucketts, even in the midst of unpacking, they have got one eye on the future.

Tim Luckett:I wanted to grow into a house and just keep growing as my family grows, instead of going and get this big house and pay all this money that it’s not even worth, just to say we got a big house. Like, no.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:They’re renting the other side of this duplex to help build equity toward that dream home. But the dream of equity across Minnesota’s housing landscape seems nowhere near striking distance.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Minneapolis.

William Brangham:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A Widening Disparity

The sharp rise in home prices across the country continues to hurt first-time homebuyers. It is widening an already large disparity in homeownership between white Americans and people of color, particularly African Americans. Nowhere is this gap wider than in the twin cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, part of the NewsHour’s series Race Matters and Fred’s series Agents For Change.

The Luckett family recently became homeowners in North Minneapolis against tall odds.

There’s a severe shortage of homes, which has driven prices to record highs.

“The way that we accumulate wealth in America is largely through our homes… If you weren’t allowed to buy in more affluent neighborhoods, if you weren’t given preferential pricing on your mortgage, if you bought a home and you had it taken away through eminent domain to build a freeway, you have been disadvantaged over and over and over.”