RAY SUAREZ: Now, safeguarding ancient knowledge in a digital library in India. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from New Delhi.

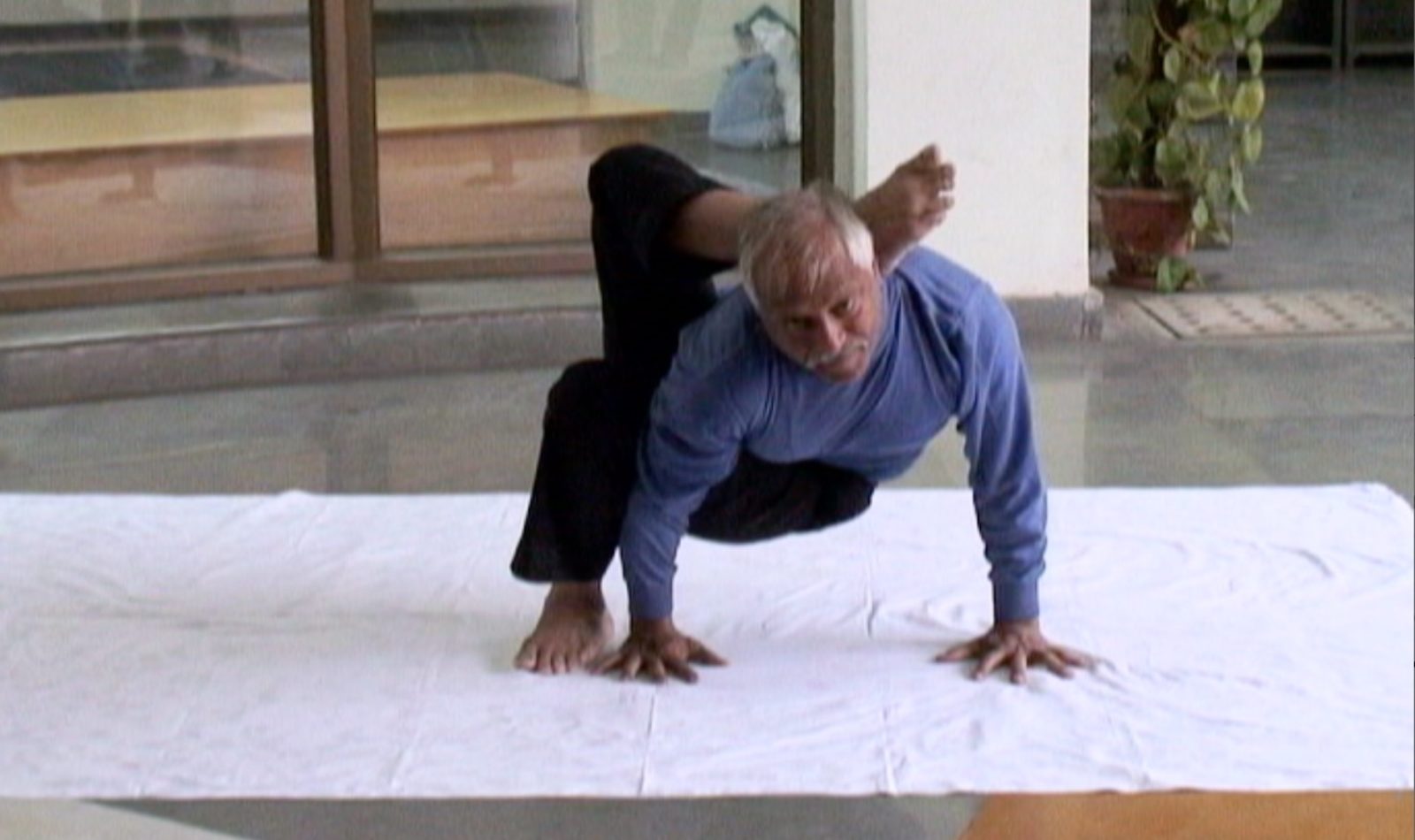

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, NewsHour Correspondent: The healing art of yoga goes back thousands of years in India. But over the past three decades, it’s become a billion-dollar industry in the U.S. Yoga guru Balmukund Singh is proud of the Indian export, but when he hears that some asanas, or postures, have been copy-written by Indians who have moved to the U.S., Singh gets, well, forgive me, tied up in knots.

BALMUKUND SINGH, Yoga Guru (through translator): This is our cultural heritage. It’s ours. How can anybody else patent this? If they invent it, they can patent it. But this is originally an Indian thing. Our sages long ago developed and demonstrated it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s not just yoga. In 1997, a Texas company got a patent on basmati rice, which meant that it would get a royalty payment when anyone else sold rice by that name. The Indian government filed 50,000 pages of evidence to show that basmati rice grown in India for centuries was essentially the same stuff. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office finally revoked the basmati patent in 2001.

India’s markets are filled with herbs and plants that, over the centuries, have been concocted into remedies for almost every ailment. It’s a medicine chest that Dr. V.K. Gupta says is raided all the time by companies and individuals in the West.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

NewsHour correspondent

In the ’90s, two Indian-American university researchers got a U.S. patent for turmeric, saying they’ve discovered its wound-healing properties. Once again, India’s government fought to have the claim invalidated.

Elements of Indian culture

V.K. GUPTA, Director, Traditional Knowledge Digital Library: Every year, at least 2,000 wrong patents are getting awarded on India’s system of knowledge, like turmeric for wound healing, which should not get granted.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The turmeric refers to is a mainstay of Indian cooking, but for centuries turmeric has also been used for medicinal purposes, applied to skin rashes and wounds.

In the ’90s, two Indian-American university researchers got a U.S. patent for turmeric, saying they’ve discovered its wound-healing properties. Once again, India’s government fought to have the claim invalidated.

Dr. Gupta says the problem is patent offices depend on accessible, understandable documentation to check on the validity of a claim. And that’s just what India’s government, under his leadership, aims to provide.

It’s called TKDL, Traditional Knowledge Digital Library. The ambitious project began in 2002 and is transferring 5,000 years of ancient texts onto a digital database in Hindi, English and eventually French, Spanish and Japanese.

Dozens of scholars spend their day pouring over photocopies of ancient manuscripts. They’ll eventually catalog architecture, music and the arts, but the first task is formidable enough: medical knowledge. There are three main healing traditions reflecting India’s varied history and geography.

There is Unani, a system begun in ancient Greece, developed later by Arabs, and brought to India by traders and rulers. Unani texts can be in Persian, Urdu, or Arabic, all sharing the same script.

Nearby are desks for Siddha, a medical science developed in south India. These texts are in Tamil. On the other side is Ayurveda, in the ancient language of Sanskrit. Tens of thousands of drug formulations, or ingredients, are buried in verse, says Dr. Jaya Saklani Kala.

Dr. Jaya Saklani Kala

Ayurvedic Physician

Earlier, what the teachers, arajayas, used to do was, they used to transfer the knowledge orally.

Archiving 30 million pages

DR. JAYA SAKLANI KALA, Ayurvedic Physician: Earlier, what the teachers, arajayas, used to do was, they used to transfer the knowledge orally.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So it was put into verse form so that the students could read them?

DR. JAYA SAKLANI KALA: Easily memorize them. Later on, it was penned down.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Some 30 million pages will eventually go from pen to hard drive. If a patent office in the West gets an application, they’ll be able to check this new library for existing knowledge, or prior art, before granting a patent.

V.K. GUPTA: Through the route of TKDL, now we are giving access to the patent offices, several patent offices we are in dialogue with — instead of stealing, we want to have a system when both collaborate with each other.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Not everyone is that optimistic. There’s worry that putting the knowledge in one place will make it easier for those looking to steal ideas. And when there is a false patent claim, poor countries simply won’t have the means to challenge it, says Devinder Sharma, an activist on biotechnology issues.

Devinder Sharma

Trade Policy Activist

Thousands of patents are being drawn every week in America on plant-based remedies and plant-based products.

Preventing exploitation

DEVINDER SHARMA, Trade Policy Activist: Thousands of patents are being drawn every week in America on plant-based remedies and plant-based products. What happens is that, when the company draws a patent, you know, and somebody challenges it, then you have to go on building up a huge battery of, you know, not only lawyers with them, but also a whole lot of research to challenge those cases in America.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For his part, Dr. Gupta says patent offices will be better able to police false patent claims themselves by using the new library.

V.K. GUPTA: No patent examiner would ever like to grant a wrong patent. It is not in his interest.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: At the same time, he says access to the library will be strictly limited and regulated to prevent unscrupulous exploitation.

V.K. GUPTA: We will draw experts from all disciplines. Our view is for every country who is the holder of such resources must designate a national competent authority of experts and that authority must negotiate with the user of that knowledge so there is some level playing field.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ultimately, Dr. Gupta hopes joint projects with drug and biotechnology companies can revitalize research in India’s traditional systems, which languished under British colonial rule. In time, he says, the marriage of ancient plant-based remedies, the library will catalog at least 150,000 of them with modern biotechnology, and create effective new drugs for the world and an economic bonanza for India.

Step one in all of this: The library on traditional medical knowledge, including yoga, is expected to be complete by the end of this year.

Tradition takes on patents

A new digital library in India is safeguarding ancient knowledge from patents, which can force royalty payments for knowledge that is common in that part of the world.