Judy Woodruff:The Batwa people, once known as pygmies, are one of the oldest surviving indigenous tribes in Africa. Their traditional lands, forests high in the mountains, straddle several East African countries.But the Batwa are now also called conservation refugees, as governments scramble to cope with the pressures of population growth and climate change.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has this report from Western Uganda.

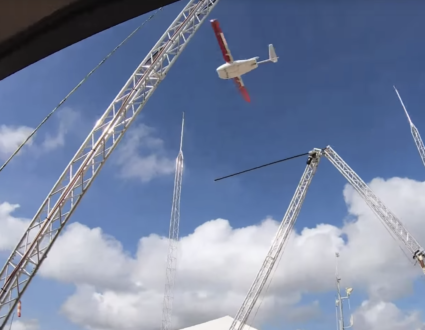

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Every morning, these Batwa men offer tourists a glimpse of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle they remember from their childhoods, starting fires, hunting, harvesting traditional medicinal plants in the forest.The forest here is also the last remaining habitat of the fabled mountain gorilla, habitat that’s been steadily lost to human encroachment in recent decades. The Batwa lived alongside gorillas since the beginning of time, these men say, but, today, they are some of the last survivors with any memory of it.In 1991, the government of Uganda reclassified lands the Batwa had lived on for millennia as national parks. That decision pitted the interests of a largely invisible people against those of an animal that had become a global icon for environmental conservation.Sixty-year-old Stephen Serutokye (ph) still remembers what the Batwa call the eviction like it was yesterday

Boas Muhumuz, Uganda Wildlife Authority:They will point their guns like this.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Our guide, Boas Muhumuza of the Uganda wildlife authority, translated.

Boas Muhumuz:Sometimes, they could scare them by shooting up in air.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Today an estimated 6,000 Ugandan Batwa live on the periphery of the forest, pushed higher and higher up the mountainside, or in slums in nearby towns.They are among the poorest inhabitants of one of the world’s poorest countries, laboring on nearby farms or performing for tourists when they can. Those who do receive a portion of the park entry fees. No tourists mean no pay. And, during the pandemic it’s often been that way. On this day, it was just me with my team.Cut off from the forest and traditional medicines, their numbers have declined. Four in 10 children don’t survive to age 5 and average life expectancy for the Batwa is 28 years, 28.

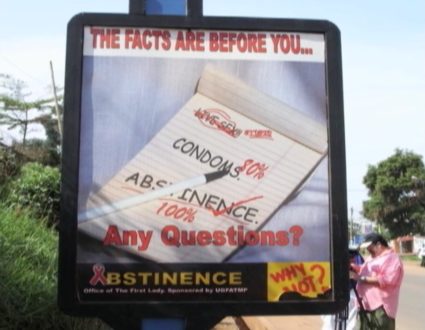

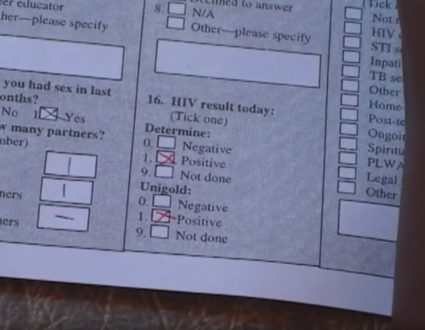

Dr. David Bakunzi:Malnutrition, and then pneumonia, then respiratory tract infections. And then the most challenging now is HIV and AIDS.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dr. David Bakunzi says the Batwa face widespread discrimination in larger Uganda society in general and in seeking services like health care. So his church-based group brings basic medical care to slum settlements like this one, where he gave me a tour.We talked to the baby’s grandmother, Justina Neirkundi (ph). Each day, she goes to the nearby town looking for farm or domestic work, usually in exchange for food. When that doesn’t work out, she’s left to beg for it, as she had for this porridge she had given an older grandchild.

Dr. David Bakunzi:She say that, yesterday, she went to somewhere where they had a party, so they give her this, and she brought it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:She went to some richer person’s house where there was a party?

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And so these are leftovers.

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes. Yes. Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The day we visited, she’d had no luck.

Dr. David Bakunzi:She has not gotten work. They have to sleep on an empty stomach.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Sleeping in cramped quarters wide open to the elements.It’s probably eight feet by four feet.

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes, something like that.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For a family of five to sleep in.

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes. It’s really very challenging.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:That’s one word for it.Even the rare bright spots, like a healthy baby girl amid so much suffering and high infant mortality, even these small victories can be short-lived, he says.

Dr. David Bakunzi:There is a risk of her getting HIV as soon as she is 10, 11, because they have lost hope.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dr. Bakunzi says many young women are forced into sex work to survive. He has 16 HIV patients in this slum community of about 90 families, a community that endures much more.

Dr. David Bakunzi:Drug abuse.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Is there is a big problem with alcoholism?

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes, yes, there is, because they don’t have work to do anywhere, especially men. They say: I have to drink and forget my problems.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:His organization, affiliated with the Seventh Day Adventist Church, is working to train Batwa to farm, to help them become more self-sufficient.

Dr. David Bakunzi:Yes, this becomes a starting point. And at a later time, we will be providing also vegetables, then beans, and soybean. They do well here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:His group rents this land for the Batwa, land that was once thickly forested, where their ancestors lived until a few decades ago.The irony is not lost on Brian Atuheire Batenda with the African Initiative on Food Security and Environment.Brian Atuheire Batenda, African Initiative on Food Security and Environment: Projects such as those are very important. But whose land was it? I’m not saying there’s nothing being done. I’m only saying that all those things are relief-based.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Relief-based help, instead of real development.

Brian Atuheire Batenda:Yes.

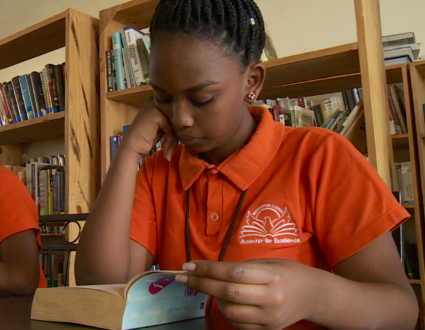

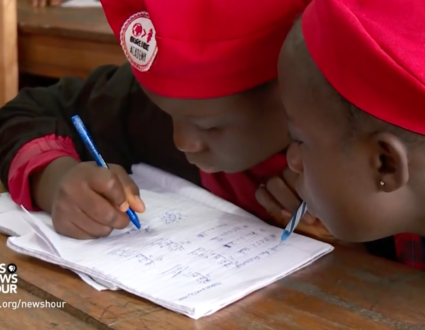

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Real development must begin with education to overcome decades of neglect, says 33-year-old Alice Nyamihanda. In 2010, she became the first member of the Batwa tribe to earn a university degree, thanks to sponsorships from aid organizations

Alice Nyamihanda, Batwa Community Activist:My people are suffering. That’s why I studied. I wanted to be an example to my people.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:She took us to visit her people in a mountainside village. Here, children are miles from any school, she says. Even minimal fees and the required uniforms are out of reach. Barely 10 percent of Batwa children are enrolled in school, she says.Advocates have taken their case to Uganda’s courts, which have ruled that the Batwa are entitled to compensation for the loss of their land. However, few people we talked are sure that relief will come any time soon or what shape it might take.One big problem, because of their small numbers and discrimination, the Batwa have little political power, says Alice Nyamihanda.

Alice Nyamihanda:We need representatives to represent the Batwa at a national level, even at all levels. Even at the village level, we don’t have someone.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:“We were evicted from the forests,” they sing, “and now they are home to the mountain gorillas.”And unlike these conservation refugees, the gorilla population has grown from 400 to about 460. But the Batwa see very little of the tens of millions of dollars Uganda earns from tourism revenue.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro near the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park in Uganda.

Judy Woodruff:Difficult story. So glad that we can tell it.And Fred’s reporting, as we always remind you, is in partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

People vs. Gorillas

are an indigenous people who traditionally lived high in the mountains across several East African countries – but that land is also the last remaining habitat of the fabled mountain gorilla, habitat that’s been steadily lost to human encroachment in recent decades.

Today an estimated 6,000 Ugandan Batwa live on the periphery of the forest, pushed higher and higher up the mountainside, or in slums in nearby towns.

They are among the poorest inhabitants of one of the world’s poorest countries, laboring on nearby farms or performing for tourists when they can.

“We need representatives to represent the Batwa at a national level, even at all levels. Even at the village level, we don’t have someone.”